Reflections on the 2022 International Conference on Food Futures

by Timothy Seekings and Chiahua Lin

Contents

Reflection on the Conference

This essay was inspired by the 2022 International Conference on Food Futures, held between August 31 and September 7 at the National Taiwan Science Education Center in Taipei. The Conference was the most recent annual meeting of the Humanities for the Environment (HfE) Global Network of Observatories[1], which is a “global organization of observatories working together to mobilize the arts and humanities,” with the goal of “address[ing] social and environmental challenges in civil society and academic life”. There are currently eight observatories in this global network (Asia Pacific, Africa, Australia Pacific, Circumpolar, East Asia, European, North America, and Latin America). The directors of these observatories gathered in this event to discuss not only global partnerships and solidarity, but also how to build a global network while collaborating with local communities.

The conference examined a wide array of issues surrounding food sovereignty, land and sea rights, legacies of colonization and slavery, dispossession, food insecurities, etc. It featured pre-conference workshops, keynote and plenary speeches, roundtables, panels, and post-conference field trips. These seven days of rich conference program brought together scholars from Africa, the Americas, Australia, Europe, the Pacific Islands, and Taiwan to discuss food and food systems from humanities-led perspectives while also incorporating insights from natural and social sciences, societal engagement, and global intervention. The conference invited attendees to envision and put into practice an interdisciplinary approach to investigating and taking on the challenge of food sovereignty and food justice.

"These seven days of rich conference program brought together scholars from Africa, the Americas, Australia, Europe, the Pacific Islands, and Taiwan to discuss food and food systems from humanities-led perspectives..."

Issues of agriculture and farming were thereby as important as food preparation and experiences of tasting and eating. Accounts and analyses from high-income, Western, and large societies were complemented and contrasted with those of low-income, non-Western, and small societies/communities. In addition, the perspectives from academia were complemented with the perspectives from the lived experience of Indigenous, local, and other knowledge systems and traditions. This is one reason why the walking workshops, the Indigenous food experience, and the post-conference field trips were invaluable elements of this conference.

In the remainder of this essay, we will first reflect on the keynote and plenary speeches[2] by Joni Adamson, Steven Hartman, and Poul Holm. This is followed by a general reflection on the role of the humanities in addressing the topic of food. Finally, we reflect on the philosophy of the Tao writer, activist, and scholar Syaman Rapongan.

Keynote and Plenary Speeches

The first keynote speech by Adamson was titled “Confronting Syndemic: Indigenous Scientific Literacies, Food Sovereignty, and the Literature of Intergenerational Justice.” In her talk, Adamson foregrounded the ideas of food and intergenerational justice. She offered inspiration for thinking more deeply about how academics can work with local and/or Indigenous communities to combat syndemics like Covid-19 and diabetes. In this time of severe global challenges, the value of the humanities lies in its constant problematizing of pertinent issues to probe the intricate relationships and the enduring quest for equality and justice. Providing examples of the projects administered by the Observatories of the Humanities for the Environment Global Network, Adamson examined how the humanities not only contribute but are well positioned to lead sustainability science and thereby ensure positive influence at both the global and local scales. Literary study, as Adamson demonstrated in her talk, becomes a force in food and intergenerational justice that cannot be ignored. Adamson ended her talk by proposing that we should build “humanities-led communities of purpose.” This kind of community takes “knowledge achieved or promoted through…interdisciplinary engagements” and mobilizes it for “genuine transformative change”[3]. Through conversations with scholars from different disciplines as well as local/Indigenous communities at the conference, participants were inspired to think profoundly about how scholars from the humanities can help engender these “genuine transformative changes.”

The idea of a “community of purpose” was also discussed by Steven Hartman in his plenary talk titled “Future Challenges of Food and the Humanities: Mobilizing New Communities of Purpose.” In the talk, Hartman highlighted examples from projects run by different observatories to discuss how humanities-led communities of purpose can push the limits of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Hartman suggested the conference as a place where new communities of purpose can be developed in which humanists of different disciplines come together to think about food-related issues and practices. A case in point was the scholars of gender, racial, and Indigenous studies who contributed to investigations of food futures from their distinct perspectives. Following this, the question is, how can feminists, activists, and practitioners be brought together to form new communities of purpose? What will these communities look like? What “genuine transformative changes” can be achieved through these communities? These were some of the salient questions emerging from the conference.

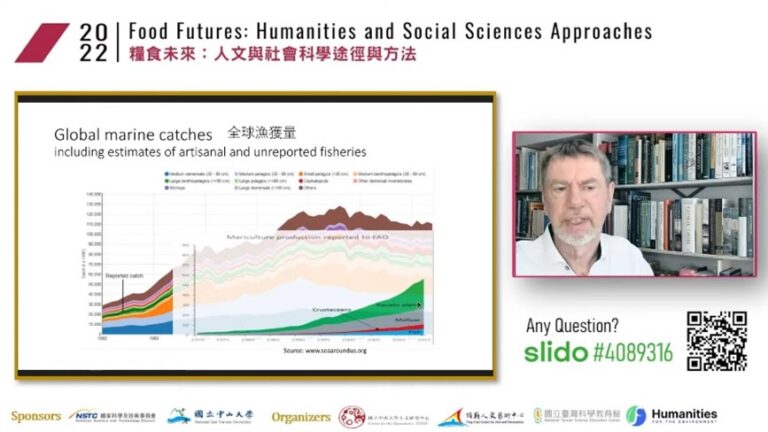

Poul Holm’s keynote speech was titled “FoodSmart Cities: A Framework for Sustainable Seafood,” in which a central proposition was the idea of consuming seafood from lower trophic levels. This can be promoted by rediscovering historical cultural practices through participatory and inclusive community-based work and using local marine resources more consciously. Although Holm employed the FoodSmart City framework in Dublin, Ireland, as the main example, his emphasis on cultural practices and local marine resources served as an inspiration for thinking about how Indigenous communities and their traditional environmental knowledge can aid in making more sustainable (sea)food consumption choices and lead to better management of (marine) ecology and resources.

Food from the Perspectives of the Humanities

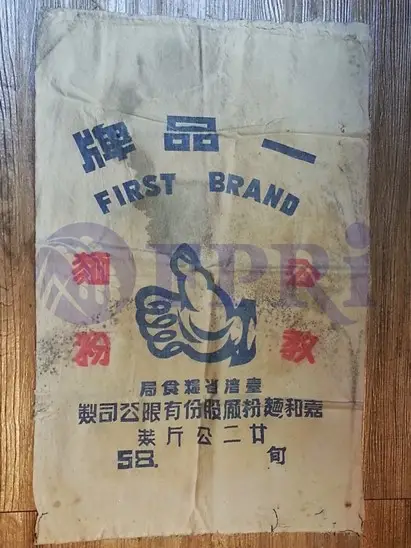

Food is a source of biochemical nutrition and pleasurable eating experiences, but for humans it is much more than that. Food is how we come to identify who we are, where we are from, how we choose to live, and what future we anticipate. Food is inextricably interwoven with our cultures, our ideas of status, as well as our ethics and morals. Through food and the means of producing it we express the ideals that underpin our relationships with each other, to the world at large, and to the transcendent or the divine. In addition to the social and institutional dimension, there is the individual aspect of food. It shapes our biography and is an important strand of our memory, reaching back to childhood and the earliest impressions of the food we grew up with. Food thus comes to represent our upbringing and our family’s particular tradition and thereby constitutes the roots to our intergenerational heritage. We are what we eat, we define ourselves by how we eat, and, in turn, we eat according to how and who we want to be, in terms of identity, status, health, and cultural expression. We do so consciously and unconsciously, being shaped from within and from the outside, by strong biological, social, cultural, and environmental forces.

"To reduce food to a question of biological survival...is at the very least a failure of the imagination and at worst, dehumanizing."

However, as Steven Hartman argued, in important global literature on food systems and sustainability at the science-policy interface, the humanities have traditionally been marginalized, and overshadowed by discourse from the natural and technical sciences. This is regrettable, as a discourse that omits the rich cultural and symbolic meanings of food and food production is incomplete and therefore unable to address the crucial issues at stake in their entirety. Solutions that are based on reductionist science and economic imperatives but that do not take into consideration the idiosyncrasies of distinct human cultures are similarly inadequate. For example, stakeholders in the alternative protein movement, who build on the idea of molecularized food to feed a growing population, favor food solutions that provide the necessary nutrition, scale up, and are easily integrated into existing industrial production systems and supply-chains. However, while these solutions look like food, many are actually hi-tech products[4]. The most advanced of them are tech tech-based, genetically engineered, and patent-heavy investments. They might satiate the body, but whether they satisfy the other expectations that humans have from their food remains to be seen. As we come to understand through the humanities, for humans, food is not just nutrition. It is equally—if not much more—about value and meaning. To reduce food to a question of biological survival, or what Giorgio Agamben calls “bare life”[5] is at the very least a failure of the imagination and at worst, dehumanizing.

"Humanities for the Environment is building pathways to enable contribution of the rich accumulated tradition and understandings of the humanities to environmental discourse..."

As food crises worldwide have now established, shortcomings in global food systems cannot be solved with technical fixes alone. Any approaches that seek to inspire sustainable change and resilient solutions must include investigations into the depth and breadth of extant food cultures including unfamiliar traditions, such for example edible insects[6]. They also must consider the rich and diverse understandings generated over many decades in the humanities (and related social sciences: anthropology, history, philosophy) and through immersive and ethnographic work. For this reason, Humanities for the Environment is building pathways to enable contribution of the rich accumulated tradition and understandings of the humanities to environmental discourse (from policymaking to pedagogy) at the international level, for example through the BRIDGES coalition[7]. As insinuated earlier, hereby the study of food and food systems constitutes a particularly pertinent field as it is perhaps the only study field that embodies not only the material and symbolic dimensions of food but also integrates the diversity of cultural understandings and experiences of food with the deep unity that originates in the shared dependence and appreciation of food and the need to create sustainable and resilient food systems in this time of change and transformation, the Anthropocene.

In sum, the humanities must be involved in discussions on food systems and sustainability to engage in the co-production of holistic knowledge, facilitate the synthesis of perspectives and approaches, and achieve integrated outcomes and solutions that are not just systemic, but, perhaps more importantly, also dedicatedly humane.

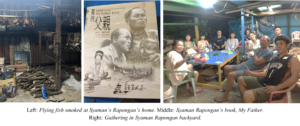

Reflection on the Getting the Fish and the Sacredness from the Ocean: Reflections on the philosophy of Syaman Rapongan

In this part we examine and interpret one of the key ideas of the Tao writer, activist, and scholar Syaman Rapongan, which he conveyed in his keynote titled “Food and Sacred Ocean Space.” We suggest that while his idea originates in Tao culture, it is valuable beyond the Tao tradition because it expresses what we understand as a core human ontological condition, which is that we inhabit both a corporeal and a spiritual (non-corporeal) reality and have to navigate and “manage” both with equal attentiveness, care, and dedication.

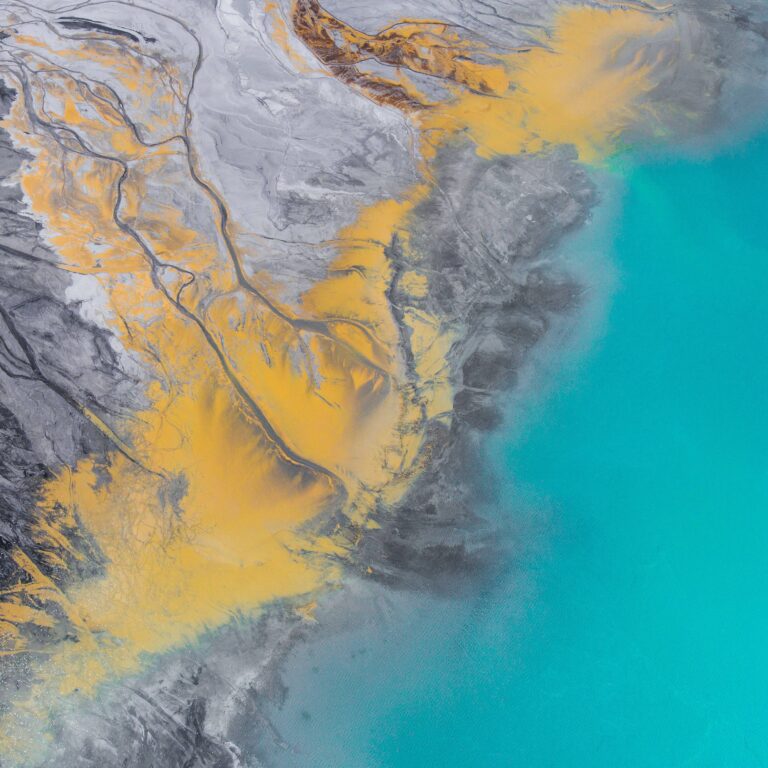

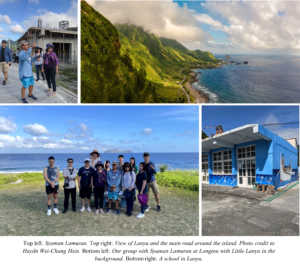

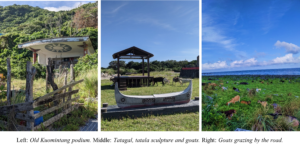

Syaman Rapongan spoke about fishing on his native island of Pongso no Tao (Orchid Island, politically part of Taiwan) and how he builds his own fishing boat over periods lasting several months. He spoke about how before he fells the tree that he designated for the construction of the boat, he speaks to it and tells it in gratitude that it is alright, that it should not worry and just “let go” in the hands (embrace) of Syaman, and that it will soon be seeing the ocean in the form of a boat. In other words, he comforts the tree that is destined to be felled by communing with it. He noted that it is important to treat all living beings with respect and care and consider their autonomous and sovereign existence. The boat that he builds is a tatala, a small rowing boat, large enough to fit him and his son. He goes out at night and fishes in the traditional way. Some others, he told us, use motorized boats to go fishing. The important thing is that the fish that are caught using the motorized boats are not the same as those caught using the traditional methods, not in the sense of the species caught, but in a sense that has to do with the sacredness of the ocean and the idea of the sacred in general.

"...with a large boat and a drag net you can get the fish out of the ocean but not the sacredness...not the deeper meaning and spiritual connection that comes with the traditional method."

In his talk, he repeatedly referred to the sacredness of the ocean and illustrated it in various ways. He sees himself as part of an oceanic people, kin with the Pacific islanders and other Pacific nations[8]. He recounted that he was once onboard a large fishing vessel on Taiwan’s west coast that used a drag net to catch fish. It might seem efficient, he pointed out, but the key point was this: with a large boat and a drag net you can get the fish out of the ocean but not the sacredness. In the same way, the fish caught by traditional methods are not the same fish as those caught by new methods and with the help of engines and technology. They might get the fish out of the ocean, but not the sacredness, not the deeper meaning and spiritual connection that comes with the traditional method. If this does not make sense immediately, let us present some brief examples that will help to embellish this central idea.

Some Terrestrial Allegories

Remember the first summer job you had or when you worked for the first time and later received the wages for your hard-earned work? This money, the remuneration, carried meaning, because you worked for it and you feel that you earned it and you deserved it. Perhaps you labored an entire day in the sun for it; perhaps you spent a week designing a web page or doing data entry. It doesn’t matter. What matters is that you engaged in a certain work that yielded an expected reward. You worked for it and you felt proud of it. Now, by contrast, if you happened to find the same amount of money on the road, if someone gave you that amount, or if you unexpectedly won it in the lottery, the money wouldn’t feel the same. It wouldn’t be the same money. It would not embody the same sense of achievement or merit or pride. It would represent the same monetary value, but it would not carry the same mental and symbolic meaning.

Or, if you prefer, imagine you baked a loaf of bread. You kneaded the dough with your hands, proofed it, baked it, let it cool, waited; then you cut off the first slice, spread butter on it, and finally, took a bite. In this scenario, your body is eating the physical bread, but at the same time your mind is eating the mental bread, which includes the process, the sense of achievement, the satisfaction, your skill, your labor, happiness, the heritage of the bread recipe, the memory of your grandmother’s bread, the symbolic meaning of bread in your culture and the significance of you practicing that tradition, etc. By contrast, someone could present you with an absolutely identical loaf of bread bought from a shop. If you ate that, it wouldn’t be the same bread. You would be eating physical bread but not mental or spiritual bread. It simply wouldn’t feel the same.

"...the products of our labor, and in an extended sense, of our method, elicit distinct feelings and senses. In other words, the method we apply lays the ground for distinct ways in which relations manifest..."

If you’re into gardening, imagine growing tomatoes. Well, to cut a long story short, the fruit that you planted and cared for over a long period of time will never be the same as the comparable fruit that you bought in a supermarket. Examples could be added ad infinitum. The point is that the products of our labor, and in an extended sense, of our method, elicit distinct feelings and senses. In other words, the method we apply lays the ground for distinct ways in which relations manifest – between us and the “products” of our labor, between those products and their environment, between us and the environment, between us and our ancestors, our values, our life, our ideas about the sacred, the divine, the world, etc.

A Sacred Method?

All these examples highlight the role of method in giving meaning to the substance, of imbuing material with spirit or of eliciting the particular spirit that the material carries as a potential. Therefore, when Syaman states that the fish that is caught by traditional methods is not the same as the fish that is caught by modern methods, and that the drag net can get the fish out of the ocean but not the sacredness, he expresses a certain transcendental ontology, what Escobar[9] describes as neo-realism, which is related to the idea of the sacred. According to this idea, all things exist on the one hand as physical objects that are embedded in a physical ecosystem and history and, also, as mental or spiritual objects that are embedded in a spiritual ecosystem and history–the socio-cultural symbolic world for us humans.

The physical reality of the fish connects us to the ecological and metabolic history and fate of the physical fish–the food that the fish ate, and the food that fed its food and so on; the evolutionary history of the successive iterations of this species of fish until the emergence of the specimen that ends up in the net, etc. In complement to this, the spiritual reality of the fish connects us to the social and spiritual history and fate of the fish–the fact that previous iterations of this fish’s lineage already interacted with the ancestors of the fisher, that the two, to some degree, shaped each other in a symbiotic socioecological relationship; and the lives of the ancestors and the ways in which they related to this fish species, their values and, connected to that, their worldview concerning themselves, their relation to the ocean and their place in the world.

It is hard to conceive how a reductionist materialist science can accommodate such a relational, holistic, and transcendental approach in its explanatory or predictive frameworks. In short, science is often said to be “the view from nowhere.” By contrast, Syaman Rapongan’s view is the unique view from Syaman Rapongan. But he himself is more than Syaman Rapongan (literally meaning, father of Rapongan as Tao people name themselves after their firstborns). He is a part of a continuous strand of intergenerational, multi-species, oceanic relationality. He is not universal. He is unique. His view is not “from nowhere,” his view is from the unique transcendental relationality that he manifests in his being, and his method serves to reinforce his being in precisely this unique manner.

"Method not only matters, it makes all the difference..."

He uses the example of the fish and highlights the role of the method of fishing as the means for transcending the mere physical quality of the fish and engaging with its spiritual dimension, and thereby with his own spiritual dimension, which is connected to that of his ancestors, and through that, with the transcendental or sacred. Method, in other words, not only matters, it makes all the difference, because everything that we interact with has a transcendental nature–physical and objective on the one hand, and non-physical and subjective, on the other. Every action we take is likewise transcendent. It affects the physical world, and it also affects the non-physical world, which, in the Tao tradition, might be understood as an intergenerational, interspecies, ocean-mediated, temporal dimension[8] . The right method, by implication, allows an individual to interact with the physical dimension of the world while simultaneously facilitating engagement with the equivalent spiritual dimension, and this is essential if we as humans want to achieve harmony within and between both dimensions.

Later in his talk, Syaman Rapongan also quipped that this was the way he fished but that he couldn’t say for sure whether what he engaged in was in fact future food or past food. Well, as they say, wise people hide the truth in jokes. With this remark he expressed another important idea, namely that in addition to being the key to the sacred, the right method is also the key to the past and to generational continuity[8] or collective continuance[10]. That’s why tradition, traditional knowledge, and traditional practices are a central axis in human navigation. This idea of continuity is just another way of saying that the future is the continuation of tradition. If we want to imagine our food future, therefore, we must look at our food tradition; it reveals where we are headed. In other words, if we want to determine our food future, we must practice our food traditions, which means living the tradition and using the proper method.

"If we want to imagine our food future, we must look at our food tradition; it reveals where we are headed."

A popular saying expresses a similar idea: “Be mindful of your thoughts, they will be your words. Be mindful of your words, they become your habits. Be mindful of your habits, it will be your destiny.” The right methods, as described by Syaman Rapongan (felling the tree with respect, building the boat, going fishing in the traditional way, etc.), allow not just connecting to the physical world and catching a fish. They also allow connecting to the spiritual world and to the original thoughts that form the tradition and that enable catching the meaning and sacredness that are the soul of the culture. The actions become the destiny. The right method naturally enshrines the existing and lived food tradition as the food future that can be expected.

Conclusion

Syaman Rapongan’s emphasis on method thus inspires us to be attentive to our own ontologies and the way in which they express the transcendental nature of being and being in the world. For example, we can find a very similar idea in the Christian tradition that is conveyed in the story where Jesus, tempted by Satan to turn stone into bread, replies that “man lives not of bread alone,” thereby emphasizing the need for spiritual in addition to physical nourishment. All this suggests that sustenance should always be sustenance for the body and for the soul. Agriculture should always be engaging with the body of the land and with the spirit of the land. Hunting should be hunting for game and hunting for meaning. And, as in Syaman Rapongan’s example, fishing should be about pulling a fish out of the ocean and pulling the sacredness out of the ocean. There is always a right method to achieve such transcendental engagement and action. However, in the modern world, it seems, we have forgotten many of these methods. We have industrial and scientific knowledge systems that produce lots of material but preciously little meaning. We have technologies that allow us to get plenty of resources out of the land and oceans but preciously little sacredness. This is our ailment and our predicament.

"[We] need to cultivate a certain humility that would enable us to admit that we might be wrong...that we might want to try and save ourselves from our hubris..."

The quest then is to learn and (re-)discover the right methods and apply them in our actions to remedy the imbalance between the material and the non-material and thereby revitalize the spiritual and the sacred. We doubt that it is technology that is central in achieving this. Rather, we as proponents of the Modern, Western, science-based, reductionist, Cartesian, or materialist worldview need to cultivate a certain humility that would enable us to admit that we might be wrong–perhaps in some things, perhaps in many things–and that we might not be the savior of the world, but that we might want to try and save ourselves from our hubris and a harmful reductionist ontology–“the story of separation[11]” as it has come to be called by some writers. Such a project has already begun, and it is visible in the endeavors to appreciate other knowledges, epistemologies, and ontologies and learn from them. Peoples and cultures exist that have been on this planet for far longer than us and who have nurtured deep understandings of the human condition and life. We should continue to learn and become even more attentive. In Zen there is a saying that if you are a good student, everybody becomes your teacher. We know that there are many such teachers in the world today, Syaman Rapongan and the Tao being one of them. Therefore, the most important thing for us to do now is to continue to learn and strive to become good students.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the organizers and conveners of the 2022 International Conference on Food Futures for their work in organizing the Conference, to Dana Powell for her valuable feedback to the first draft of this essay, and to Hsinya Huang for support and guidance.

About the Authors

Timothy Seekings Currently a PhD candidate in Natural Resources and Environmental Science at the College of Environmental Studies, National Dong Hwa University, Hualien, Taiwan. He was born and raised in Germany, completed his Bachelor Degree in International Relations and applied Sociology at London Metropolitan University and his Master’s Degree in Humanity and Environmental Science at National Dong Hwa University. His current research is an action research project about edible insects and sustainable food systems. Recent publications include Learning the nature of Language[12] , The proof is in the cricket: engaging with edible insects through action research[13]. Other academic articles and essays can be found at https://ndhu.academia.edu/timothyseekings, and creative and experimental writing at https://paradigmlost.substack.com/.

Chiahua Lin Currently a Ph.D. candidate in the English Department of the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. She is the recipient of 2018 Fulbright Graduate Study Grant as well as the 2020 Government Scholarship to Study Abroad (GSSA) from the Taiwanese Ministry of Education. Her research interests include Trans-indigenous Studies, Ecopoetics, Hawaiian Literature, and Pacific Literature. She currently works as the secretary for the Asia Pacific Observatory of Humanities for the Environment. She is the co-editor of Chinese Railroad Workers in North America: Recovery and Representation (2017) and Pacific Literature as World Literature (2023).