Even a Blade of Grass

[quote author=”Henry Miller” ]

“The moment one gives close attention to any thing, even a blade of grass, it becomes a mysterious, awesome, indescribably magnificent world in itself”

[/quote]

I grew up in many places. With an English teacher for a mother and a veterinarian working for the United Nations for a father, my childhood was as necessarily transient as their professions. When we returned to Canada, my mother’s and my birthplace, I finally spent enough time in one location to grow roots. Don’t get me wrong, I loved traveling—I loved moving from country to country with the land and plants and animals changing as quickly as my address—but there was something about being rooted that felt comforting, even if I didn’t feel quite like I belonged.

My family now owns a farm in North Western Ontario. It’s not a working farm, more a small collection of ramshackle barns in various states of disarray, and then, fields. 125 acres of boreal forest trimming four open fields. A lining of rich green spruce trees and elegant white poplar and birch frame a wide open space where foxes slink, deer startle, and hawks circle above, every now and then plummeting to the earth after a vole. In the winter, this shining expanse of white snow ices over so that you can wander atop the drifts, listening for that telling crackle that will sink you up to your thigh. Here and there, dead grass peaks out from this blanket and small tracks offer a sign that even at 40 below, a hidden life is thriving.

Photo taken by Megan De Roover

The fields aren’t planted or maintained—unless you include the neighbor that comes every few years to bale hay for his cattle. They’re not homogenous by any means, just residual open spaces where flowers and grasses and grains all intermingle. And where, if you look carefully, on an early summer’s day, you can find tiny wild strawberries deliciously peeking out between strands of green. Day Lilies, Blue Eyed Grass, New England Asters, Devil’s Paintbrush, Birdfoot Trefoil and Daisies of all colours dot the green and gold expanse, and a set of packed dirt tire tracks lead the explorer through.

Photo by Megan De Roover

Even our lawn is multicolored with flowers that my father painstakingly mows around, leaving tufts of Black Eyed Susans along a meandering shorn path leading nowhere.

Now fields might not be the most exciting thing about the “great white north”—in fact, when we think of fields we tend to think of them as empty space, defined by their lack. But this place was alive in ways I’d never experienced. Staying in one place for longer than a year or two offered me a whole new world of watching. The rapidity of travel and the vast distances that I covered at frequent intervals in my childhood had left me a bit lost. Extended travel by plane shifts your perception of time because of how the body “does not move but is moved” (Solnit 28). It wasn’t until I had the time to start walking that I was able to begin re-scripting the spaces where I lived, and engaging with them in a more meaningful way—noticing for the first time the details of the local environments, the weeds coming through the gravel driveway as distinctive species. Rebecca Solnit argues that being moved rather than moving creates a division between the embodied understanding of place and where one is. But then, from this Canadian wilderness on the edge of the largest fresh water lake in the world, I came to Arizona. I’d visited before, but this move was different.

I arrived at my new apartment with only a handful of photos and an email correspondence. I’d selected it for two reasons, the first being that while dozens of other apartment blocks wouldn’t give me the time of day, this complex was comprised almost exclusively of international students attending Arizona State University. The other reason was that while perusing online photos of residences with my mother, we’d both exclaimed “oh look! Green!”

Photo by Megan De Roover

A patch of green lawn and a few cotton wood trees immediately made this place my new home for the next several years. Somehow, as long as there was a little bit of green and a little bit of water, the transition to come here felt easier—even though my objective and sustainability-oriented mind conflicted with my desires. I longed for green while in the desert: wasn’t this at odds with my values? Shouldn’t my aesthetic appreciation shift according to location? I like the way the desert looks and feels, but I can deny the comfort seeing that green patch gave me upon my arrival.

In addition to this discomfort raised by my own longing for green, I found out that bermudagrass, the species commonly used for lawns in this region, is an invasive species, first arriving in the Americas in the 1750’s through contaminated hay used for bedding in ships on the transatlantic slave trade (Kopec). It is a guilty pleasure, seeing it through my window and walking over its dewy blades each morning, knowing that both it and I share a contentious relationship when it comes to belonging and this place. After learning more about its scientific background[i] (which you can locate by scrolling down) it became important to me to find the local grasses of this region and to see how the invasive and the indigenous interacted.

When I’d set out to find an indigenous grass, I assumed that it would be a fairly simple task to locate it. After all, grass is ubiquitous, isn’t it? Everywhere in the Phoenix valley there are green lawns of bermudagrass and Winter Rye grass, as well as ornamental fountain grasses decorating most neighborhoods. I naively thought that some indigenous grass would make up the background scenery on which these foreign species were foregrounded.

I underestimated the skill of bermudagrass in populating this area. It has a mind of its own, like the species in Michael Pollan’s The Botany of Desire, which have gained global control by feeding our human desires for sweetness, beauty, intoxication and control (apples, tulips, cannabis, and potatoes, respectively). Where would grass fit into this scheme? Perhaps beauty, since it has come to define urban aesthetics through the invention of the lawn, or perhaps control—of the local environment, and of our movements. “Keep off the grass” signs dot this country, shaping our movements until, as I’ve noticed, we avoid walking on grass out of habit. Lawn grass has rooted itself in the American psyche, shaping urban design more than we give it credit for. Not only this, but lawns have come to stand as a framing device for how we define our homes; lawns are a luxury and a structure to how we define home. Variations on this lawn motif greatly impact how we see ourselves. After all, the neighborhood policing that goes into lawn maintenance certainly says a lot about how we interpret the people around us.

Lawns, as an ideal, must be a particular color, free from weeds, neatly maintained by largely unseen workers, coming together to tell a story of environmental control and wealth. In many residential districts of Phoenix, home owners are required by law to appropriately maintain lawns in order to adhere to the neighborhood aesthetic—a feat that requires considerable time and money to mow, water, and reseed when the weather gets too hot or cool for that species. As Robert Nixon says in his book Dream Birds, “desert money is a universal currency: it is always blue and green” (74). In this book he talks about the first introductions of bermudagrass to this region, primarily through Alexander John Chandler’s introduction of lawns for golf—a sport previously played on the dirt in this area. Interestingly Chandler was responsible for creating the aesthetic maintained today in the Phoenix metropolitan area largely because he wanted to draw on a tourist base from his home country of Canada. When I’d first read this, I was stunned. It was as if the appeal of the green lawn at my apartment had been deliberately constructed to draw me here. Admittedly there were many other factors resulting in my move, but the coercive lure of grass played a larger role than I was at first willing to admit. Once I learned about bermudagrass–memorizing its distinctive growing structure so that I could spot it even after the lawn mower had its way–I could see the wide distribution everywhere.

I set out to find an indigenous grass (with no particular variety in mind) in order to study the local to the invasive. Unsettled by the manipulation I felt at the hands (Blades? Roots?) of bermudagrass, I longed for something less controlled. This was nearly impossible—an outcome I hadn’t considered. Almost everywhere that indigenous grass would otherwise be located, invasive species had taken over, due to human efforts or otherwise. The problem was being able to find native species in this desert of homogeneous lawnscapes.

Everywhere I looked, all I saw were the invasive species of bermudagrass and its ilk. At first, I blamed the bermudagrass. How dare it take over the territory by horticultural conquest? Frustrated, I walked about the neighborhood glaring accusingly at these neat lawns, stomping past them on the sidewalk, searching for something else. I had to admit, however, that as frustrated as I was, both this lawn and I shared something. We are both immigrants to this place, sharing the title of invasive species. Elizabeth Kolbert argues in her book, The Sixth Extinction, that having invasive behaviour is both our best and worst trait as humans. Although we might not like to think of ourselves this way, it is evident that humans are one of the most invasive species on the planet. We have spread across the planet, displacing other species and colonizing members of our own, and not only have we done this, we’ve done it with gusto. Whatever it might mean for other species’ survival, ours has been ensured by this practice. As I wandered through the suburban lawns of Tempe, the bermudagrass passing by my feet, I saw a reflection of myself. I did not find any indigenous species of grasses on that day, nor have I yet in my neighborhood.

Kolbert has an article in the New Yorker called “Turf War” in which she questions why the West has such an obsession with the particular aesthetic of the suburban lawn, explaining that “over time, the fact that anyone could keep up a lawn was successfully, though not all together logically, translated into the notion that everyone ought to” (Kolbert n.p.). The sweeping proliferation of lawns certainly attests to this statement. I mentioned this article to my partner, Sven, an environmental engineer in Canada, to which he responded, “Turf war? Like rival gangs?” Even though the play on words is amusing, I started to wonder what it would be like if the actual grasses were the rival parties fighting over territory.

I asked Sven, “Can you imagine if they were rival gangs? What they would say?”

“Grasses can’t speak,” he replied.

But grass speaking isn’t such an outlandish idea if you consider than many indigenous cultures have sacred plants that are given voice in stories. It’s only in the strictly scientific model that the thoughts and expressions of plants and animals are disregarded—a model that is significantly lacking because of this restriction. We learn so much from the exercise of listening, whether this is through imaginary or literal conversation with other beings. While I have no heritage of stories with grass as the protagonist, I could still imagine what that might be like. Combining turf wars with the recent invention of twitter wars, I speculate it could go something like the following. First, let’s meet the characters.

There’s Bermudagrass:

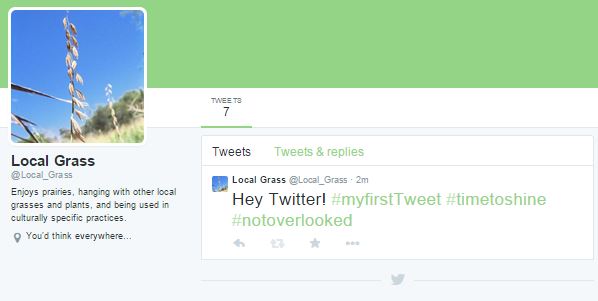

And then a LocalGrass:

And their conversation might go something like this:

While this is overly simplified, the similarities between outside conquests over indigenous territories in grasses and humans are unmistakable. Even now, golf courses spread out over territory originally belonging to the various first peoples of North America, often provoking land claim disputes. One of the most well-known disputes would be the Oka crisis in 1990 which took place between Mohawk people and the Quebec town of Oka. It was spurred on by the townships plan to expand into territory traditionally held by the Mohawk by creating an expanded golf course and residential housing development. There had already been earlier legal contestation over the original nine hole golf course but “authorities and the courts dillied back and dallied forth, and in the meantime, the developers went ahead with the construction of the course, and happy golfers began roaming up and down the fairways in their little carts” (King 233). And the area on which this golf course and its expanded 18 hold version would occupy? A sacred pinewood grove and an ancestral burial ground. While Tom King’s The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America is primarily about indigenous peoples, the issues surrounding land claims in his chapter “As Long as the Grass is Green” is the principal source for all social disputes in North America. The fundamental difference for King is that “land has always been a defining element of Aboriginal culture …[so] land is home” while “for non-Natives, land is primarily a commodity, something that has value for what you can take from it or what you can get for it” (218). While he admits that this might be a gross generalization, societally it rings of truth. Just look at the circumstances of the Oka crisis with sacred land being traded in for golf courses. Even as I disparagingly shake my head at the colonial legacy of land as an inanimate object I can once more recognize myself—or at least, the comfortable privilege granted me by such a historical trajectory—in it. But maybe there is something more to this idea of “land is home” that could apply more broadly to humanity. After all, I already noted that something about grass makes me feel at home. Maybe recognizing that is a first step towards something.

Even without the violence of land claim disputes, it is obvious who does or does not belong on a golf course. Membership fees, equipment rentals, and dress codes all help to police who is using the sprawling space. Even as this benign lawn expands in otherwise seemingly empty desert, it is clear that there are politics at play that work to maintain an economic social structure.

Photo by Megan De Roover

In Andrew Ross’ Bird on Fire: Lessons from the World’s Least Sustainable City journalist Andrew Kopkind of The New Republic is quoted as saying “Apartheid is complete. The two cities look at each other across a golf course” referring to Phoenix and Scottsdale in a 1965 (Ross 116). Ross’ novel is a critique of the Phoenix valley’s city infrastructure in relationship to water resources. Although grass is not mentioned frequently, it is always present in discussions of water allocation. Charles Bowden, a well-known Arizona author and journalist, wrote his first book Killing the Hidden Waters on the same issues of environmentalism in the South West. Water and grass are never far from each other in these conversations, although, for the most part, the grasses being critiqued are the invasive lawn or turf grasses. Centering on the golf course, it’s evident that the homogenous expanse of invasive grass is a barrier, socially and ecologically, with very real consequences. As Richard L. Duble states in his article on bermudagrass, “The Sports Turf of the South,” “the variety of names given this species attests to its wide distribution and to the fact that it is the object of abuse and scorn … including “Kweekgras” (S. Africa), couch grass (Australia and Africa) [and] devil’s grass (India)” (Duble). The proliferation of bermudagrass as an invasive species used in sporting turf and golf courses produces all kinds of interpretive biases, especially since it is so adept at crowding out other plants (explaining why it is selected for homogenous lawnscaping). But is the title “devil’s grass” really necessary? There’s nothing inherently evil about this species. In fact, it has been incredibly successful in populating the globe–just like humans.

Photo by Megan De Roover

Even as I critique bermudagrass and the golf courses it calls home, there are undeniable benefits which complicate the easy assumption that invasive is a negative name. After all, wasn’t I drawn to that luxurious green to begin with? Didn’t I enjoy watching Inca doves and grackles wander through the emerald blades, hunting for insects or bathing in pools of sprinkler water. Didn’t I love sitting on it with a book, or rolling around with the dog I watch every so often? But aside from personal reflection, there are still scientific benefits. Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect is a very real fact of living in the greater Phoenix area, and interestingly, turf has a useful impact on this phenomenon. As Anthony Brazel explains in an online Arizona Republic article from 2007, “heavily irrigated residential areas are coolest, due to both the evaporating surface water and the shading effect of trees”. Brazel has numerous articles and studies on this topic, all focusing on UHI in Phoenix and potential improvements at policy levels. Interestingly, the residential areas to which he refers are areas like my own neighborhood that frustrated me so much. While I was busy bemoaning the lack of indigenous grass, I overlooked the fact that the grass that is there aids not only my survival in this city, but a whole host of animals that might not be able to endure the heat unmitigated. In fact, I’d overlooked the very thing I’d set out to bring to the foreground—it was a shameful realization.

Still unable to find an indigenous species in my area, I set out to escape from the lawns and golf courses to the Phoenix Valley Desert Botanical Garden in search of the elusive grasses of Arizona. I trekked to the Plants and People of the Sonoran Desert trail, hopeful to finally find in this section a variety of indigenous grasses. This was easier said than done. Even though an entire section of the trail is considered Semidesert Grassland, only five plants were labeled, and only one of those five was a grass (bear grass, that while technically a grass looks like a small spikey shrub). While the entire area was covered in three separate varieties of grass, none of them were immediately recognizable.

Photo by Megan De Roover

I gained a new found admiration for these desert (or Semidesert) grasses, particularly for their hardy ability to survive the baking Arizona sun. My plan, when I had arrived, was to sit in the shade and spend an hour contemplating this species with calm, meditative thoughts (starkly contrasted from my frustrated city wanderings). Alas, as picturesque as my communing with grasses had been in my mind, I was rudely confronted with my own bodily constraints. While I sweated through my shirt, vainly trying to replenish my body by guzzling bottle after bottle of now warmed water, these grasses swayed in the barely perceptible breeze, coolly regarding me (I imagined) with a level of disdain. Not only was this a disruption of my somewhat poetic envisioning, I was continuously distracted by the various fauna wandering through the area. I nearly stepped on a mourning dove while walking, and then (to my delight) found an entire family of Gambel’s quail murmuring softly in the underbrush. Even when I had set my pack down and pulled out my notebook, an absolutely stunning Blue Spiny lizard plonked himself on the rock that I had been eying as a seat. As I catalogued these animals, I was attuned to the fact that even in a situation where my undivided attention was supposed to be focused on grasses, I was simultaneously seeking a more anthropomorphic encounter. With renewed purpose, I set about photographing and examining closely the grasses I could find.

The three grasses in the semi-grass land section all grew mixed in with one another but could be differentiated by the thickness of their blades and stalks, and, more noticeably, their seeding formation, as documented in the images below. Of course, all of these grasses grew together in the same area, intertwined with one another so that upon my first glance, I could not distinguish more than one variety. With further research and the aid of the DBG’s PlantHotline I have now been able to correctly identify each one as indigenous Southwest grasses. As I wandered through the clumps (off of the trail, but careful not to trample the specimens) I began to see the three varieties as clearly as any combination of garden flowers.

Sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula):

This grass has thin bright green blades, of no more than half a centimeter wide, and seed stalks that featured individual tan colored seeds alternating along the flowering culm. The elegant column neatly dangles the seed pods as it stands erect in the field.

Cane Beardgrass (Bothriochloa barbinodis):

Photo by Megan De Roover

The second grass is considerably thicker, in both the width of the blades and the stems (particularly near the crown, or base) with a deeper shade of green and distinctive fluffy seeds. The light colored seeds immediately catch the eye in the desert sun as bright spots dotting the field, enticing me to feel softness of the seeds and the texture of the stalk between my fingers

Green Sprangletop (Leptochloa dubia):

Photo by Megan De Roover

The third species also has a thicker base stem and was less prolific in the grassland area. The seeds are delicate tendrils, very similar in some respects to the invasive bermudagrass often used in the valley for turf and lawns. The familiarity of this grass was curious because of its resemblance, and yet the differences (such as the height and texture) held my attention.

Because I had no way of immediately identifying these different grasses (I researched and added names and details after the fact), I drew my first associations between them and my memories. Cane Beardgrass brought back the small fluff my pet hamster used to make a nest, and Green Sprangletop conjured a practical joke my mother had used on us kids. My mother, a long time teacher now turned daycare administrator, was the one who instilled in me an appreciation for the environment (as well as the one who bought me my first hamster). As a youth I was constantly dragged from one course to the next, joining organizations like FEEA (forum for ecological education and action) and attending retreats where I was always the only non-adult. Perhaps I didn’t show my appreciation at the time (do teenagers ever do that?) but it stuck with me, and I kept going. Only recently we took nature kindergarten training together in Scotland. But besides being a friend and mentor she was also a trickster, constantly finding the fun in whatever activity we did, no matter how mundane. While walking along the path through the field, she would pluck two seed stalks of a grass very similar to Green Sprangletop and tell us she had a surprise. I remember her leaning in front of me, her eyes twinkling behind large glasses and the shock of white hair that hangs over her forehead, placing the crisscrossed strands between my teeth. “Smile!” she said, and then pulled on either end, seeds filling my mouth and teeth, while she and my brother roared with laughter. I remember it took what felt like forever to get those seeds off my tongue. But it was pretty funny.

While that joke is something I look back on fondly and fully intend to use on my own children, the most visceral reaction I had was when I saw sideoats grama for the first time. Its slender stalk and delicately placed seeds reminded me of the grain fields in the prairies. As a child, I’d spent several summers visiting my Nanny and Papa in the province of Saskatchewan, where so much of the terrain and experience is defined by wheat fields and the prairies. We’d spend most of our time making rounds to farms owned by distant family I didn’t know where, uninterested in the conversations happening at the kitchen table, I’d wander about the fields, running my hands over the tall golden stalks. Once, I convinced my grandmother to let me catch a pair of prairie dogs that would have otherwise been killed by the farm hands. My father built a pen for them and my Nanny—who I imagine will never quite forgive me—had to drive me and the pair of smelly rodents for a full three days back to Ontario. After that incident, my visits were more subdued, though I still wandered the fields. This “Land of the Living Skies,” as Saskatchewan is sometimes called, for me was defined not by the powerful atmospheric shifts that give the province its catchphrase, but rather by those delicate stalks bending gently beneath my palms like spun gold. Well, that as well as the less poetic shrieks that came from my Nanny when she thought one of the prairie dogs had escaped in the motel room.

While Cane Beardgrass, Green Sprangletop and sideoats grama are all worthy of their own individual studies, sideoats grama is particularly interesting. This particular grama grass has significance in multiple cultures for many reasons, ranging from its attractive seed stalk structure to its nutrient content.

Without being able to go directly to elders with firsthand knowledge about this grass, I researched through ethnobotanical databases for recorded accounts of traditional uses and stories surrounding sideoats. The Native American Ethnobotanical Database (NEAD) through the University of Michigan has a convenient listing of recorded uses by anthropologists and ethnobotanists of both indigenous and settler communities. Links to this database and the National Park Services “History and Culture: Grasses, Shrubs and Trees” can be found in the works cited. Both databases offer records of sideoats having been used in medicinal, veterinary, symbolic, and ceremonial uses. I use the past tense here only to refer to these sources as historical archives (the earliest study being from 1939 with the most recent from 1964), since some of the practices are most likely at least partially maintained by the communities in question.

Plains Apaches used sideoats in a “medical procedure to remove cataracts from the eyes” while the Kiowas used it for fodder for their horses. The Kiowa also used the seeded stalks ceremonially to refer to having killed an enemy with a lance due to its “resemblance to a row of feathers hanging along the edge of an Indian Lance” as elaborated by the Encyclopedia of Earth website. The beautiful appearance of the seeds dangling off of the thin stalk that I found so gentle and attractive now associated with violence. Other groups “used dried stalks of sideoats grama to make brooms and hairbrushes” (eoearth.org). In a more romantic NEAD entry, “Young Lakota women searched for four-headed spears of grama grass to bring them good fortune in love and romance,” but according to the National Park Service article, “Only the Lakotas, Kiowas, and Plains Apaches are reported to have had use for these grasses.” I have yet to find a four-headed spear, but Sven assures me that I don’t need to. There is some criticism for these source materials since each story is sourced with an anthropological endeavor—none coming directly from the peoples themselves. There are movements in ethnobotany with focus on indigenous storytelling and culture coming from the communities and peoples themselves, but not much has been published on sideoats.

Most popularly known for its status as ‘State Grass’ in Texas, sideoats is indigenous to a wide area of grasslands in the Americas, ranging from Canada to Argentina. Perhaps I’d even seen it before, ran my hands over its unique seed structure before, a long time ago in the Canadian prairie. Its large seeds feed a variety of wild animals as well as forage for most livestock due to its high nutrition value and its ability to grow in otherwise harsh conditions (plants.usda.gov). Both bermudagrass and sideoats are used in warm season forage, and being perennial come up naturally for livestock each year (aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu). Because of the physiology of bermudagrass, the very reasons why it is an adaptable and useful forage grass are what make it invasive. Its system of stolons and rhizomes quickly crowd out other forage grasses such as sideoats which rely on a different root system, as can be seen in the following diagrams. A deeper analysis of stolon and rhizome systems can be found by scrolling down.

While both grasses serve similar functions in the world of livestock rearing, it’s clearly evident that one is invasive and the other indigenous. The distinct lack of the native sideoats in areas it once profusely populated is indicative of a larger, highly problematic, endangerment of native grasslands.

Ethnobotany and literature could be a means of addressing the endangerment and the preservation of indigenous grasses, particularly through the dissemination of stories. Although grass is more often than naught a backdrop in stories (as well as images, sports—in fact, it’s almost always in the background, we just never talk about it) there are a few examples of grass being foregrounded.

Brian Patten’s poem “A Blade of Grass” exchanges grass as a living poem which he then tries to articulate in a poem himself.

You ask for a poem.

I offer you a blade of grass.

You say it is not good enough.

You ask for a poem.

I say this blade of grass will do.

It has dressed itself in frost,

It is more immediate

Than any image of my making.

You say it is not a poem.

It is a blade of grass and grass

Is not quite good enough.

I offer you a blade of grass.

You are indignant.

You say it is too easy to offer grass.

It is absurd.

Anyone can offer a blade of grass.

You ask for a poem.

And so I write you a tragedy about

How a blade of grass

Becomes more and more difficult to offer,

And about how as you get older

A blade of grass

Becomes more difficult to accept.

An unlikely subject for a poem, the grass Patten is offering becomes a beautiful and poignant critique on how people will often dismiss its beauty, its poetry, while searching for something else. I found myself in this same position before I began to really look at my surroundings and see the grass for what it is: “more immediate/than any image of my making” (Patten).

Grass, an often overlooked backdrop, when brought to the foreground becomes a being of extreme beauty. Sideoats captured the imagination of warriors and lovers in Kiowa and Lakota tribes, while bermudagrass became the art of the elite in landscaping. It appears that grass is in fact a prolific source of art, both in poetry as I’ve just articulated, but also in visual art, sculpture, and performance. In all of these cases, grass is transformed from the mundane into the extraordinary, much like the quote by Henry Miller that begins this article.

Andy Goldsworthy is a well-known British artist based in Scotland who works with sculpture, photography and the environment, making ephemeral visual art in both urban and rural spaces. The works of art themselves (which you can see on his website goldsworthy.cc.gla.ac.uk) are made with natural, often found, materials, and once created and photographed, are left to disintegrate. Some of his most compelling pieces involve grasses woven or grown into intricate patterns, making this simple and often overlooked species an aesthetic wonder. Teaching programs like Voices from the Land bases itself in Goldsworthy’s artistic practice as a way of educating school age children about ephemerality and caring for the environment. When I took this teachers training program in Thunder Bay (this was one of the programs I attended with my mother), it was striking how often we don’t think of our environmental surroundings as art. It was also remarkable how easy it was to change this line of thinking. We spent hours lost in our art making in a small grove of trees and brush near the road side, finishing with a “gallery walk” of all of our creations. The creativity and the excitement was refreshing, and even though this program was designed for school aged children, I think every adult present enjoyed themselves immensely.

Crop circles are probably the most popularized and sensationalized art form that uses grasses as its primary medium. While the grass is usually not the focus of the art, there is much speculation on how grass can be manipulated into creating the massive visual art forms. Whether these designs are extra-terrestrial or a human construction is up for debate, making crop circles the subject of dozens of documentaries, books, horror films, and science fiction novels. The crop circle as art is interesting because it draws a mystical aura of the uncanny and the beautiful to the often overlooked and mundane. The ongoing controversy of the “authenticity” of crop circles offers an unusual platform for discussing grass as an aesthetic and (surprisingly) mysterious art. In documentaries like Crop Circles: Mysteries in the Fields, MIT students create crop circles to explore the mechanics surrounding this peculiar anomaly, while still fulfilling the stereotypical extraterrestrial conspiracy rhetoric in a titillating genre.

English Crop Circle Formation (no copyright)

Not all art surrounding grass is quite as exceptional in terms of its physical transformation of the raw materials as Goldsworthy—who weaves and manipulates grass—and crop circles—which are made up of bent or disturbed grass. Sometimes all that is needed to draw attention to this grass is to place it physically in an unusual place. Performance artist Vaughn Bell’s work “Playing with Plants” offered a transformation of plants by giving them movement. His theory was that by mobilizing otherwise rooted and overlooked beings, we can gain a new understanding of them. Some of his work involved creating plant ecosystems in shopping carts and then pushing these wild grasses around suburban lawns, and others involved placing potted plants on wheels to be “walked” like dogs on leashes. What if we gave plants the same attention that we give to other favourite household pets?

While I don’t think I’ll be taking my house plants out for a walk anytime soon, it does make me wonder what other possibilities there might be to bring these overlooked species to the attention of the public. I imagine that most people are under the impression (like I was when I first began) that indigenous grasses are everywhere, precisely because they don’t know how to identify them, or, only considers grass as a carpeted mass for other, more interesting things, to stand on.

Grasslands cover one third of the Earth’s Land Surface … and The North American prairie is one of the most endangered ecosystems on earth. The grasslands of North America began to form about 20 million years ago, but in some areas up to 99 percent of the prairie has been destroyed (in just the last 125-150 years) (www.statesymbolsusa.org)

The eradication of indigenous species of grass is particularly noticeable in the Phoenix Valley, for even areas where indigenous grama grasses were once plentiful, such as along the Salt River where they served an important function against erosion, they have vanished. The absence of grama grasses creates a deficiency in nutritional foods for animals that benefit more from sideoats than bermudagrass (such as birds). It is a loss that is hidden behind the acres of tidy green squares that define this city.

Even as I revel in the feeling of dew (more likely the automated sprinkler, but dew sounds nicer) on my toes as I walk about my bermudagrass lawn in the morning and fully accept my own appreciation for its uniform greenness, I can no longer interact with it without being acutely aware of how its presence indicates the absence of other varieties. Then again, I cannot deny its own usefulness in my life as it aids in making the summer temperatures bearable. How do I begin to negotiate this complicated relationship that leaves me lost for words? As Lyanda Lynn Haupt writes in The Urban Bestiary,

I absolutely believe that guilt cannot be the highest or even the most efficient motivator. Attending the world more closely, we are inspired to act instead from a sense of love, interconnection, and a recognition of mutual strength and frailty. (305)

Instead of a condemnation of human behavior that improperly pits one species over the other, there should be an emphasis on offering new models of thinking about our relationships with our environments, developing into what Haupt calls “a new nature”. For myself, going through these ethical gymnastics reminds me of the first three rules in Charles Bowden’s rules of the border:

YOU ARE IN THE RIGHT PLACE.

YOU DO NOT BELONG HERE.

DEAL WITH THIS FACT. (Inferno 35)

Like the bermudagrass, I must accept that while I am invasive, I am here. Perhaps my ‘dealing with this fact’ is to “attend the world more closely” and “act…from a sense of love” by continuing to investigate these two grasses that define my living experience of the Southwest and bring the overlooked into sight—whether that species is one that is lost or one that is demonized (Haupt). Perhaps it is to accept a more complicated position that does not resort to a hierarchic dichotomy of good or bad.

If lawns define the aesthetic of the urban spaces I have lived in, what about sideoats? Something about it reminds me of that wilder place, those fields where I learned to grow roots. Something about it offers more than the cut and combed plots of land that are alluring only in their flatness and shade of green. There is texture in the indigenous grass that is perhaps more wondrous because of its sparseness, a pleasure in finally discovering it hidden away on a corner of the botanical garden, and a sadness knowing it once reigned this place.

Chandler’s plan to lure Canadian snow birds to the South West worked—the migration to the golf courses is a measurable shift. And it worked for me when I clicked on that apartment listing. It made me feel more comfortable through the recognizable continuity of green in a place otherwise alien to my ecological experience. It wasn’t this proliferation of bermudagrass that made me feel at home though—after all, home didn’t have neat green lawns. Finding sideoats was like finding home in the desert, achieving what bermudagrasses could not. It was not a tree or a landscape or anything so obvious, but that subtle background, that gentle grass that I’d overlooked until I’d lost it to a sea of lawns.

Grass defines our homes, framing them in blocks of green, carefully marking out our space in the world. But what of that grass that strays beyond our control? What of that species that ranges wild across the prairies? Is it really any better or worse than the one that creeps stolons across the sidewalk despite our best efforts? While I found sideoats to remind me of home and childhood, that block of green which I so readily critiqued turned out to be a lesson in curbing my own divisive thinking. In either case, I cannot imagine home without them.

Photo by Megan De Roover

Works Cited

- Bowden, Charles and Michael P. Berman. Inferno. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006. Print.

- Brazel, Anthony. “Urban Heat Island Affects Phoenix All Year Round.” Arizona Republic. 22 September 2007. Web. 1 December 2014.

- Crop Circles: Mysteries in the Fields. Dir. John Tindall. Termite Art Productions, 2002. Film.

- Cudney, D.W., Elmore, C.L., and Bell, C.E. “bermudagrass.” University of California Integrated Pest Management Program website. Np. Nd. 2 September 2014. Web.

- Duble, Richard L. “bermudagrass: The Sports Turf of the South”. Texas Cooperative Extension. Np. Nd. 2 September 2014. Web.

- “Excerpts from Killing the Hidden Waters.”The Charles Bowden Reader. Eds Erin Almeranti and Mary Martha Miles. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010. Print.

- Gilmore, Melvin Randolph. Prairie Smoke. Bismarck, North Dakota: N.p., 1922. Print. Goldsworthy, Andy. <http://www.goldsworthy.cc.gla.ac.uk/>

- Haupt, Lyanda Lynn. The Urban Bestiary: Encountering the Everyday Wild. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013. Print.

- “History and Culture: Grasses, Shrubs and Trees”. National Park Service, Web. 8 October 2014.<http://www.nps.gov/wica/historyculture/upload/-14C-Appendix-B-GrassesShrubs-Trees-Pp-891-939.pdf>

- Kolbert, Elizabeth. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2014. Print.

- Kolbert, Elizabeth. “Turf War.” New Yorker, 21 July 2008. Web. 8 October 2014. <http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/07/21/turf-war-2>

- Kopec, David M.. “The History of bermudagrass”. Cactus Clippings: 9.1. University of Arizona. Web.

- Leimkuehler, Ray. Desert Botanical Garden. Plant Hotline Correspondence. September 9-11, Web.

- Native American Ethnobotanical Database. Dearborn: University of Michigan, 2005. Web. 8 October 2014. <http://www.maquah.net/BritBrn/ethnobotanical/Bouteloua.htm>

- Nixon, Robert. Dream Birds: The Strange History of the Ostrich in Fashion, Food and Fortune. London: Doubleday, 1999. Print.

- Patten, Brian. “A Blade of Grass.” Love Poems. New York: HarperCollins, 1990. Print.

- Pollan, Michael. The Botany of Desire. USA: Public Broadcasting Service, 2009. Film.

- Ross, Andrew. Bird on Fire: Lessons from the World’s Least Sustainable City. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. Print.

- Ryan, Courtney. “Playing with Plants.” Theatre Journal. 65.3 (Fall 2013) 335-353. Print.

- “sideoats grama.” The Encyclopedia of Earth. 12 September 2014. Web.

- “Side-Oats grama Plant Guide” Natural Resources Conservation Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 12 September 2014. Web.

- Solnit, Rebecca. Wanderlust: A History of Walking. New York: Penguin Group, 2000. Print.

- Solnit, Rebecca. A Field Guide to Getting Lost. New York: Penguin Group, 2005. Print.

- “Texas State Grass.” State Symbols USA. 12 September 2014. Web.

- “Vegetable Resources” Aggie Horticultural AgriLife Extension. 12 September 2014. Web.

[i] Species Case Study: Bermudagrass

Bermudagrass (Cynodon Dactylon) is a commonly used turf grass in the southern United States. Presumed to have originated from Bermuda, the moniker in fact more likely came into usage because of the grass’s association with the Caribbean and Southern States. Originally imported from Africa around the 1750’s, bermudagrass has been traced to contaminated hay, at that time used for bedding in ships carrying slaves on the middle passage route (Kopec and University of California integrated pest management program website). Since its arrival, it has been used for forage in the cattle industry as well as for lawns (aesthetic and recreational), particularly in areas with higher temperatures and direct sunlight.

Bermudagrass is able to withstand the heat and sun of the Arizona summer with appropriate watering and thus is used as a seasonal grass at Arizona State University and the larger Phoenix Valley. Due to its seasonal coloration a companion grass, Winter Rye Grass, is commonly used in Arizona, replacing the bermudagrass in late September. bermudagrass is perennial and is dormant (turning a yellow-brown) in the winter months while Winter Rye Grass (typically an annual, although hybrids exist) must be seeded every Fall. Through this process of switching lawn species, the aesthetic of year round green grass is maintained in the Phoenix Valley where the temperatures range from 7- 41 Celsius. Bermudagrass thrives specifically in 24-37 Celsius, although it can come out of dormancy in temperatures as cool as 15 Celcius.

The balance between Winter Rye Grass and bermudagrass depends on meticulous attention to temperature, height of grass, sunlight, and watering. For these reasons appropriate maintenance of lawn spaces are rigorously structured. The details of mowing and scalping lawns are intensely documented by lawn maintenance companies. Mowing is only to remove 1/3 of the grass blade at a time, primarily to maintain the aesthetic green color, as well as a manicured height. Because of high light requirements for the physiology of bermudagrass, the seasonal Winter Rye Grass must be physically removed in order to allow the dormant bermudagrass to access enough sunlight to begin its growing season properly. Therefore, a process called scalping is conducted in order to remove as much Winter Rye Grass as possible and to remove the discolored dormant blades of the bermudagrass. Scalping is mowing the grass as close to the ground as possible without damaging the surface hugging stolon system. For bermudagrass the average mowing recommendation after scalping put forth by fairwaylawns.com (to name one lawn maintenance resource) is every 3.8-5 days for a grass height ranging from 1.5-2.5 inches during its growing season. This is additionally done in order to prevent the grass from self-seeding, since during the mowing process the seed stalks are removed. Because bermudagrass is considered an invasive species, unintended seeing can create problems.

Briefly mentioned before, the physiology of bermudagrass is defined primarily by its shoots, known as stolons (above ground) and rhizomes (below ground). Stolons, also known as runners, lie on the soil surface with intermittent nodes on which new root systems (called adventitious roots) expand downwards, creating (effectively) a new grass plant. Rhizomes function as underground root systems that also send up shoots for grass. They move both horizontally (like stolons) as well as in other directions to collect nutrients. Examples of each are strawberry plants (stolons) and ginger (rhizomes). The seeding plant has stalks with two to six spokes at the top and the blades are thin, smooth, pointed, and have small white ‘hairs’ at the base of the sheath. It is exceptionally resilient in the face of high levels of light, heat, saline, and traffic, and so has been used for sports turf as well as aesthetic lawns. According to David M. Kopec, an extension turfgrass specialist, the “specialized growth stems and…relatively rapid growth rate [make this species] excellent at crowding out weeds” making ideal for homogenous lawns. These extending stolon and rhizomatic systems also allow the species to cover a wider area more completely, moving nutrients around from richer deposits to those experiencing a lack. However, for this same reason, it is often considered a weed when not in a lawn space particularly due to its ability to send stolons out over sidewalks and other surfaces.

While incredibly popular as lawn turf (aesthetic lawns, golf courses/sports fields, etc.) the bermudagrass is simultaneously considered an invasive weed that causes serious damage to other crops around the world. Its underground rhizomatic growth structure makes it difficult to remove from commercial crops such as sugarcane, cotton, corn, and vineyards (Duble) making chemical herbicides a common method of eradication. As Richard L. Duble states in his article on bermudagrass, “The Sports Turf of the South” “The variety of names given this species attests to its wide distribution and to the fact that it is the object of abuse and scorn,” “including “Kweekgras” (S. Africa), couch grass (Australia and Africa) [and] devil’s grass (India)” (Duble). In addition to the problems arising from bermudagrass crowding other plant species, the presence of this grass species also changes the surrounding ecosystem, providing a food and shelter source for many different kinds of insects. Duble lists the insects that feed on bermudagrass, including “armyworms, cutworms, sod webworms, bermudagrass mites and Rhodegrass scale (mealybug)” which feed on the foliage, and white grubs that feed on the roots. Insects that live on the grass “include chiggers, ants and ticks” (Duble) clearly make this species a veritable source of food for various urban bird species. Where the grass is left chemically unmodified and un-groomed, the tangles of the stolon can provide shelter even for small mammalians and reptiles (depending on the location and climate).