Luck of the Gecko

[quote author=”Charles Darwin”]

“At some future period, not very distant as measured by centuries, the civilised races of man will almost certainly exterminate and replace throughout the world the savage races.”

[/quote]

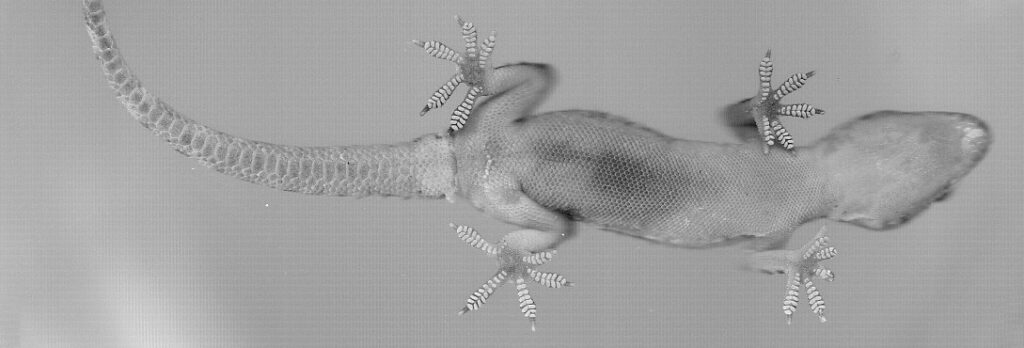

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AHouse_gecko_scan.JPG

In Miami, Florida, on the day of August 24th, 1992, my mother and father were expecting their first-born child. A week prior to this day, the city was receiving warnings of a storm that had originated from a tropical wave over the central Atlantic Ocean. Only days later, it had intensified into a category 5 hurricane that would soon become the costliest hurricane in United States history, one of the most devastating storms known as Hurricane Andrew. As a child, I remember listening to my parents reminiscing about their past, about how this one day had changed the future of our family forever. “Tell me the story,” I would beg my father over and over again. He always began the same way.

“Your mother and I we’re living in a little one-bedroom apartment in Biscayne Bay, close to the water where the storm was most expected. People all around us we’re evacuating from their homes and heading inland.” He would go on to tell me about their close friends, John and Kim, who were stuck in Indiana at the time and were unable to fly back to their home in Florida due to the increasingly threatening weather conditions. John called my father and suggested he take my mother and grandfather to their house that was located further inland to stay safe. Once they had arrived, my father hurricane proofed the house the best he could, nailing plywood to all of the glass windows. “At midnight the storm came,” he would say. He explained to me how the pressure inside a house was different from the pressure outside, and this resulted in what he could only describe as an annihilating explosion. “Everything was chaotic. I took your mother and grandfather into the bathroom where they stayed throughout the night. The noise was frighteningly loud and we could hear glass smashing and things breaking through the walls and windows. There was water pouring in from every crevice and opening. For hours I stood, holding shut a door that was between the living room and kitchen so the rest of the house wouldn’t flood. Exhausted, I decided to try and get through the kitchen and into the garage to get tools to nail pieces of plywood over the door. But once I opened the door my jaw dropped. The entire living room was wide open. The roof had blown off. There were no windows, only open holes through the three remaining walls.”

For a week they were stuck in the house. There was no water or electricity. When they finally got the chance to return to their apartment in the Bay area, they were overwhelmed by the ruinous condition of their once beautiful neighborhood. “We were completely lost. Everything was unfamiliar. I saw a street pole bent into the ground and got out to look at the sign. It was our street. Your mother and I held each other and cried.” My parents had lost everything, a lifetime of pictures and books, their every belonging. They found a place to stay for the remaining weeks not far from their apartment, where my mother soon gave birth to me. My father was working for a company at the time that had just opened up a corporate office in Mesa, Arizona. Once the company found out about my parents situation, left homeless like the 40,000 other families in Florida, they offered him a job there. My mother, father, and I left empty handed, to the place that would become our new home, Arizona.

* * *

The other morning I sat on the patio of my rickety little apartment in the college town of Tempe, Arizona, thinking about this story that I was so captivated by as a child. I thought about how my whole life would be in Florida had Hurricane Andrew never hit the coast. My life would have been completely different had I grown up surrounded by and exposed to such contrasting ecosystems from those existing in the Sonoran desert. As I sat daydreaming, a bird landed on the tall cement wall that enclosed my yard and caught my eye. It had a grey backside that darkened into a black tail, but to my surprise, its belly was a bright, radiant yellow. I watched the winged creature perched on my wall, staring cautiously into my yard. I tried to think of the last time I saw a bird that wasn’t brown, black, grey, tan, or some variation of the four. Before his pictures were lost to the storm, my father was passionate about photography and my grandfather took a strong interest in bird watching. I remember my father telling me about the beautiful photographs he took of all different bird species when he and his father would go out together with their binoculars and cameras. While I have absolutely no bird watching experience, I was intrigued and wanted to ask my father about the colorful creature. I searched the Internet and found it to be either a Western or Cassin’s Kingbird. I hoped to see it again. Perhaps spending my childhood in Florida, around other various types of colorful and more tropical animals, such an animal wouldn’t have completely consumed all of my attention. Maybe I would have grown a different understanding for the incredibly diverse types of urban animals and wildlife that I would have encountered on a daily basis. Maybe the little bird, with the bright yellow belly, would have been overlooked.

In addition to possessing an interest in photographing birds, my father has also always been passionate about other species of life. As a child, he instilled in me a sense of appreciation for learning about all forms of non-human beings. He was the person who I shared the deepest connection with and I was always eager to listen to what he had to teach me, or see what he had to show me. We spent most Saturday mornings contently watching Animal Planet, and anytime he found an interesting program or article related to wildlife, he would share it with me, explaining the parts that I wasn’t yet old enough to quite understand. He was one of the greatest teachers I’ve had, partly because we were such similar people. We were both cautious, observant, and patient, always internalizing our complicated perceptions of life, thoughts that stem from our neocortex and mammalian brains. We had an unspoken connection that he used to keep me curious and thoughtful of the world around me.

School furthered my love of learning. It exposed me to new material that I would have never discovered otherwise. When the time came for the public school system to teach us about Darwin’s theories, I fell into a fascination. I wanted to learn as much as I possibly could about every living thing. I loved how Darwin’s ideas helped me to make sense of the world. One of his quotes in particular always resonated with me. He wrote, “At some future period, not very distant as measured by centuries, the civilised races of man will almost certainly exterminate and replace throughout the world the savage races” (Darwin 193). Now in my adulthood, my love for animals has developed from more than just an interest in finding enchanting little bits of information and facts about individual organisms. It has matured into an infatuation for looking more closely at the non-human species co-existing with us here on Earth. It has become a lens for seeing how wildlife and the natural world have shaped our culture and society throughout time, and how it will continue to influence the future of mankind.

While I now live on my own as a college student, I frequently visit my parent’s house. They live in Scottsdale, Arizona in the same house that they first purchased when they arrived from Florida. This place had been my home since I was only a few months old, and it holds all of my most cherished memories. As a little girl, I remember swimming in the pool of our backyard and discovering the delicate, floating bodies of baby geckos that had met an early and unfortunate fate. Scooping them into my hands, I would let the water seep through my pruned fingers until I was able to feel the soft, tiny bumps of skin that covered their teeny frames. I would gently lay them in the rocks that lined our desert-landscaped yard, and watch how the sun shone so strongly on their pale, lemon-gold bodies that their skin glowed effervescently. Carefully turning them from side to side, I would squint my eyes and try to get a glimpse at what could possibly be inside such an infinitesimal, alien-like animal. I still find it hard to imagine that the insides of a species so different can even slightly resemble the systems keeping me alive beneath my own skin.

There was one summer day in particular, I was about 7 or 8 and brought one of the drowned geckos into the garage where my father was working on one of his motorcycles. The History Channel was playing in the background. I showed him the lizard. He was the first to tell me that it was a gecko, a type of lizard that lives in warm climates throughout the world. “The families near the lights outside our doors have been there since you were a baby. Supposedly you can hear their calls at night if you listen closely enough.” he said to me. You can click on the link below to hear the sound made by a Mediterranean house gecko. Sound familiar?

Click on the link below to hear the sound of the Mediterranean House Gecko:

http://www.californiaherps.com/lizards/pages/h.turcicus.sounds.html

“We’ve descended from reptiles over millions and millions of years,” he informed me. Even today, we still share characteristics with the closet living relatives to dinosaurs. I learned that part of what makes up the human brain is the reptilian brain. This is the most primitive structure that we share with reptiles and birds. It keeps us alive when we’re sleeping, regulates our heart and breathing rates when we engage in physical activities, and allows us to breath and digest without constantly thinking about doing so (Deming 177). In her book, Zoologies: On Animals and the Human Spirit, the well respected American poet and essayist, Alison Hawthorne Deming writes, “We are all feral children – beneath the art and invention, beneath the emotion and connection – a reptilian brain, alien and necessary, buried in the mythic and material depths of us all” (177). In a sense, our species is a compilation of those around us. Looking back at this moment and learning from my father about the family of Mediterranean house geckos that are our neighbors, I am left reflecting on our differences and similarities to the animals that live alongside us, and how our lives influence one another. It is our socialness and family ties that give meaning to our lives. My geckos may not share our mammalian brain, but does their reliance on one another give meaning to their lives, too? You can watch the incredible video below of a gecko saving his mate from a near death, and think about this question.

Long before man, the world was undergoing a number of major changes that altered the core composition of our planet. Change has been a constant in the history of all things. Today, I can’t help but wonder if I would have had a similar experience with the geckos if my family had remained in Florida, as the Mediterranean house gecko was, in fact, first reported in Key West in 1915 (Bartelt). Would I have discovered them in my backyard and curiously contemplated what connections creatures so different as human and lizard could ever share? As time passed, I began to grow into a completely different person from the little girl I once was. I was faced with the daunting task of growing up, making friends, fitting in, learning how to grow into the best self I could be. Life suddenly became more complicated and the geckos slowly settled into the back of my mind. I have realized that day-by-day my curiosity for the community I’ve grown up alongside has diminished, and night-after-night I pass by the family of Mediterranean house geckos above the door to my home without so much as a glance in their direction. I’ve become so accustomed to having them there that as my own life became more complicated throughout middle school, high school, and now college, I never really took the time to find answers to the imaginative questions I once had as a child. Reflecting on our history, however, is a provoking way for thinking about how much we share with even the tiniest living creatures.

Both science and cultural traditions can teach us that geckos and humans have expanded to explore territories that are far from, and immensely different from our homelands. Similar to humans, Mediterranean house geckos have proved themselves as pioneers of the Western frontier. As we set out on voyages to discover the new world, all different forms of life followed, and like us, many of these creatures flourished. As these new landscapes became more familiar, we made our homes and reproduced, generation after generation. Our families grew and establishments were made, and so we continued to spread, making both humankind and the Mediterranean house gecko go down in the books as an “invasive species”. Elizabeth Kolbert, author of The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, explains the term invasive species as introduced organisms that not only survives, but also “gives rise to a new generation, which in turn survives and gives rise to another generation. This is what’s known in the invasive species community as “establishment”” (201). While it is impossible to determine for sure the frequency of this event, many established species likely remain in the area where they were introduced, or they often go unnoticed. The third step of this invasion process, which a number of species go on to complete, is spreading to new locations (Kolbert 201). In many places we find ourselves, we find geckos; not only native geckos, but also various types and breeds that, like many human families, have left behind their ancestors in search of a better future. Whether we associate them with good luck or bad, knowing their history can help us to see how inherently intertwined our lives are with the past. They can help to remind us of how far we have come and how.

Like humans, Mediterranean house geckos have historically proved themselves historically as pioneers of the Western frontier. Conservation of this species is of low priority as its range and population are increasing. They are known for their rapid breeding abilities and strong resistance to pesticides. The Encyclopedia of Life justifies this conservation status by “its wide distribution, tolerance of extensive habitat modification, presumed large population, and because it is unlikely to be declining fast enough to qualify for listing in a more threatened category”. Much like us, they are always finding new ways to progress. The EOL also explains the invasive species status of the Mediterranean house gecko as a “consequence of having few predators in places where they have been introduced, and also of their tendency to take shelter in the cracks and unseen areas of human homes, for example inside walls. Reliance on human habitation has thus contributed to their proliferation, similar to rodents.” The Mediterranean house gecko is a non-migratory species, but is native to the Mediterranean and west Asia. As such successful and rapid colonizers, they have found ways of expanding their distribution with the aid of human activities. The electronic field guide, Gecko Web, refers to the reptiles as “the most successful stowaway of all North American lizards”, as they hitch onto boats, trucks, or planes, helping to explain their wide distribution. Such traits have led to steady populations of this reptile all throughout the Southern United States (Bartelt). For many experts, the mystery of how the Old-World species first made its way to the United States remains. One theory surrounding their arrival is that they were stowaways on a ship from the Mediterranean (Bartelt).

One reason the Mediterranean house gecko is so successful in colonizing new places is due to its rapid breeding abilities and strong resistance to pesticides. Such qualities have led to a low conservation status, which the Encyclopedia of Life (EOL) justifies by “its wide distribution, tolerance of extensive habitat modification, presumed large population, and because it is unlikely to be declining fast enough to qualify for listing in a more threatened category”. The EOL also discloses information about the invasive species status of the Mediterranean house gecko as a result of having few predators in the places where they have been introduced, and also because they often go unseen as they tend to take shelter in the cracks and overlooked areas of human residences. Their reliance on human habitation has therefore contributed to their proliferation, like that of rodents. The Mediterranean house gecko is a non-migratory species and they are native to the Mediterranean and west Asia. Yet, as such successful and rapid colonizers, they have found ways of expanding their distribution in many places throughout the world. The electronic field guide, Gecko Web refers to the reptiles as “the most successful stowaway of all North American lizards.” They find ways to hitch rides on boats, trucks, and planes, resulting in their wide distribution and presence, from Europe all the way to North America (EOL). There are steady populations of Mediterranean house geckos throughout the Southern United States (Bartelt), from my family’s first home in Florida, to my home now in Arizona. While their presence is an indirect effect of human activities, it is also a direct effect of our desires and decisions.

Geckos are highly popular animals in the pet-trade (Bartelt). While I mourn the loss of an intrinsic sense of curiosity that came so naturally to me as a child, I observe this inspiring quality in the children that I help care for as a nanny. Elle, an 8-year-old girl, has had numerous pet rodents, like gerbils, hamsters, and mice. She prefers critters that are a bit more furry and fluffy, like her pet ginuea pig, Sparkles. 5-year-old Will, on the other hand, is saving up for his own first pet – a gecko. Not long ago, he enthusiastically handed me a flyer of basic gecko care information, and at the top of the page there was a picture of what appeared to be a Mediterranean house gecko. Will also exclaimed that he would get crickets as an added bonus to feed his new friend. When I returned home that evening, I turned to Google to briefly research the Mediterranean house gecko as a pet. I came across a number of inquiries from the general public asking if they can be used for pest control purposes. After reading a few discussion forms, I found one woman motivated, like many others, to invest in a house gecko because she’s heard that they “are a good method of dealing with roaches”, and, she adds, “they’re kinda cute”. Another comment was from a woman saying that she recently moved states and the amount of insects around her home appeared to be much higher. She explained that she used to have geckos on the walls of her old house and believes that they drastically helped limit pests and other insects. She thought they could now be useful in her new home as well. Bringing in nonnative species, however, can interrupt the balance of the current eco-system.

Commonly overlooked species and their presence, like the gecko’s, may not outwardly appear to affect the balance of the eco-systems around our homes, but it is our responsibility as a species sharing this Earth with other forms of non-human life, to understand that each and every living creature plays a valuable role in making the environment, as well as our societies, function in a way that is both healthy and necessary. It is important both culturally and environmentally to appreciate and accept the diversified parts of the world for what they are. In doing so, we are also able to observe and admire how the earth is home to so many different and unique ecosystems. Many of our families may have traveled far from where they began, and we should embrace the diversity of life and see the different and unique regions of our planet’s differences as a reminder of the past and an expression of our present and future. Together, humanity and wildlife have traveled incredible distances, each shaping the world into what it is today.

Taking a step back and looking into our past can help put into perspective our place in the world. We can rediscover the ideas surrounding man and the natural world that have played, and still continue to play, an important part in helping us understand every species place in relation to one another. Today, our time is so often consumed in technology, work, school, and family and social obligations. It isn’t uncommon to suddenly find yourself feeling disconnected to nature and distanced even from the wildlife just outside your door. Continuing to possess an appreciation for school and my ongoing college education, I found that historical and cultural works of art and tradition offer an enlightening and grounding way of thinking about mankind and our environment. The stories of so many non-human species alongside the stories of mankind have helped to fabricate everything from our constantly crystallizing societies to our unique cultural values around the globe.

Studies in history, philosophy, aesthetics, religion, literature, film, and media, relating to the natural world have been an integral part in forming the societies of today. Further exploring the interconnectedness between culture and the natural world, Deming, writes “As long as we’ve been human, we’ve been making art. Or perhaps it is more accurate to place this eagerness to participate in creation at the center of what it is to be the animal we are: as long as we’ve been making art, we’ve been human” (8). From the beginning of time, humans have possessed a need for art as an outlet to explore and express our time and place as a society. These forms of art, whether it is through writing or oral storytelling, are a framework for people to share, examine, and question the history of all life that has fashioned the world that presently we live in. Our human cultures are a way for us to braid art, nature, and ideas of what we are, where we are, and where we want to be. Such works provoke us to reflect on ourselves as a species in relation to other species. They call attention to the differences between the human and non-human. They explore the intricate ideas surrounding how we make one another what we are, and how one can never exist without the other.

Some of the most paramount examples of humanity’s place in the natural world stem from the stories of native cultures. The Hawaiians, witnesses of the colonizing capabilities of geckos, associate them with luck. The native people of Hawaii have a great respect for these animals, not only because they are a useful form of insect control, but also because they resemble the “mo’o”, the Hawaiian guardian spirit that refers to a gleaming black, dragon-like reptile. This spirit often plays a role in their creation legends, and it ranks second to the shark (Hawaiian Life). One article I recently stumbled upon on Hawaiian mythology featured in Maui Magazine, further explains the “mo’o, saying, “Dragons. Lizards. Deities. Whatever word used to invoke them, mo’o rank among Hawaii’s most mysterious mythic creatures. They figure into the oldest Hawaiian stories and are a key to a deep, nearly forgotten magic.” In many native cultures, lizards are given the same level of importance and influence as animals that today we would likely think of as being notably more charismatic and symbolically powerful, such as a lion or polar bear. The history of human culture has the potential to teach us that all life, no matter how small or unseen, shapes the way we view the world, in turn shaping the actions and decisions we make as well. Recognizing the powerful qualities found all forms of life, not only those of charismatic species, can allow us to continue enriching our culture, while also bringing attention and awareness to the creatures that are a vital part to our diverse eco-systems and understanding of life.

Before I realized that the curiosity and more observant nature I had as a young girl for the wildlife around me was slowly fading, I can recall one night when I was still in high school that reminded me of the riveting roles that animals have played for so many different people. I was knocking on the door of my best friend, Natasha’s house. Her parents had moved to America from Pakistan, about twenty-five years ago after they were married. Natasha and I had been inseparable since kindergarten, and her family lived in the same neighborhood as mine. I considered her to be a normal, American teenage girl, no different than myself, but her parents were always foreign to me. They were always speaking to one another in Gujarati, their first language growing up in Pakistan. When they spoke English they had a thick accent and uproariously loud voices – something I dismissed as cultural. Natasha answered the door and her mother yelled at me from the living room to come in quickly so no geckos would sneak in. Recently, they had found a few geckos inside the house and thought they must have been crawling in right through the door. “They sneak in without anyone even noticing. Gross, slimy little things. Galori. They make me think of my mother,” Natasha’s mother, Spenta said.

“They won’t harm you,” I told her, used to seeing them each night outside my own doors.

“Yes they will,” Spenta replied. “They have harmed my family for generations.” She went on to tell me the story of how years ago in Pakistan, her grandmother was sitting on the living room sofa when a lizard scampered over the ceiling. “The nasty thing fell from above onto her and bit her in the chest.” About a month later her grandmother was diagnosed with breast cancer near the spot the lizard had left its mark. A generation later, Spenta’s mother also fell ill with the same, grievous sickness. I thought of the day in elementary school when Natasha told me that her mother, too, had been diagnosed with breast cancer, and again when it came back just a few years ago. To this day, lizards represent bad luck for these people, and they believe that these creatures are the reason why the women in their family have been cursed with cancer and forced to undergo such grim and terrifying times. Despite their negative connotation in some cultures, Natasha’s mother’s story is an example the powerful influences of commonly overlooked animals in native cultures and traditions that make us view the natural world and its inhabitants in a certain way. Whether their presence is a blessing of good luck, or a curse of the bad, cultures from all over the world employ legends, stories, and art that can help us see that we are living in a more than human world.

Lizards in native cultures don’t always carry a meaning associated with luck. A Native American tribe known as the Karuk, employs lizards in their stories as symbols to help explain the mysterious origins of the earth. I came across one of their creation legends in the book Spirits of the Earth: A Guide to Native American Nature, Symbols, Stories, and Ceremonies. The author, Bobby Lake-Thom, writes of the tale of a lizard and coyote working together to help make the first babies in the world. The two animals were one day discussing the problems that women were having giving birth and trying to find a solution so that they would not die. The lizard suggests that they should let the baby come out from behind, instead of from her mouth, and says that he will try to help her. The Coyote responds to the lizard in favor of his idea, but says that they should let the first baby be born a female because more good women are needed in the world. The lizard agrees, then says, “but I am going to help make the boy’s hands, feet, and penis while it is still in the woman’s stomach. And since he will then look like me, I will always make sure he is protected and grows up to be a warrior” (149). Similar to the Hawaiian creation legends, the lizard is bestowed with an important role alongside the charismatic Coyote. In this particular story, the lizard is even viewed as a warrior, vowing to protect the unborn. Also interestingly, we can see from this story that in some native cultures humans were modeled after animals. Throughout all time and until today, we can look to old stories and traditions to understand our place in the natural world.

The association of geckos and lizards with luck and positive creation stories, however, is not found in all cultures, as I have already learned from my visit with Natasha’s family, but they can still offer us great insight about ourselves. A chapter from the Kitab As-Salam, The Book on Salutations and Greetings, in the Islamic religion, says, “He who killed a gecko with the first stroke for him are ordained one hundred virtues, and with the second one less than that and with the third one less than that” (Bauer 120). Still today, we are less drawn to reptilian creatures than of more charismatic mammals because we feel so different from them. Lizards often appear portrayed negatively in many poems as well. One amateur poem I came across links our likeness to reptiles in a piece called Reptilia. It reads,

My skin feels like scales

A piano bench

Metronome passing the time

Impatiently

Perfectly

Living like death

Spreading along Petri dishes

And moving forward in octaves

Like a starving gecko

Eating its own tail

To me, this self-expression of art is an example of the common misrepresentations associated with geckos. After all, it is our reptilian brain that is constantly keeping us alive. In addition, it is unlikely that such a successful survivor with a wide variety of prey should be forced to eat its own tail to survive. Yet, it helps us to acknowledge that there is much we don’t know about the animals living around us, or even about our own evolutionary past. Aaron M. Bauer, author of Geckos: The Animal Answer Guide, writes on the luck of geckos that varies each year, “In Sri Lanka there is a long tradition of making predications based on the actions of geckos. Even today an annual almanac is published that contains the sections “predictions based on gecko calls” and “predictions based on the body area on which a gecko falls”‘ (118). These reptiles, no matter what light they are portrayed in, are full of a spiritual power that can still be seen influencing society today. However, we all too often forget to reflect upon the roles that we have given to animals throughout history, roles that help us to make sense of all that exists. Geckos, tiny and commonly unnoticed, have helped humans for a great deal of time to unlock a nearly forgotten magic. This magic, I believe, is a key for looking at our past to see how it has influenced the way we view the world. It can help us adapt a new, positive perspective for understanding the importance of every living being that keeps our planet so balanced. Taking the time to reflect on our cultural history leads to a deeper connection, and a deeper understanding and appreciation for the natural world.

It is through the past that we can gain perspective of what it means to be human in a world that is, and will always be, so inseparably connected to all that is not human. In attaining this sense of perspective, we find ourselves. We become enlightened. We are able to recognize how different life is today than it once way. The past allows us to better understand our place in the present, and we can use this recognition to help us see where are headed in the future. Henry David Thoreau, perhaps one of the world’s most famous philosophers and insightful naturalists, once wrote of the West:

The West of which I speak is but another name for the Wild; and what I have been preparing to say is, that in Wildness is the preservation of the World. Every tree sends its fibres forth in search of the Wild. The cities import it at any price. Men plough and sail for it. From the forest and wilderness come the tonics and barks which brace mankind.

I believe that not only in wildness is the preservation of the world, but also the perspective that humanity, as stewards of the Earth, must make an effort to realize for the wellbeing of all species. This wildness has become the place where we have settled down to have our families and make our lives. Today, we are often lost in the technological and scientific advancements and social constructions that society has weaved into our everyday lives. Wildness disguises itself in the cracks of our walls and the crevices of our homes, but it is always present, and always nearby. It is in our past that we can recapture a sense of wildness so remarkably pure and powerful, to see ourselves, to see our future.

Having lived apart from my family for a few years now, I am no longer greeted each night by a family Mediterranean house geckos. Each time I visit my mother and father, however, in our home filled with the memories of my childhood, I look forward to their welcoming presence. Though they are now a few generations more recent, I know that this will always be their home, too. From time to time, as I am sitting each morning on the patio of my own, makeshift home that is my college apartment, I’ll notice a lizard scamper by and think of my life here in Arizona, the only place that I have been able to call my true home for as long as I can remember. Or perhaps I’ll find myself lucky enough to be visited by a colorful little bird that will make me think of my home that could have been in Florida. I try now, to see more through the eyes of my childhood self, to embrace my own personal past and the past of all humankind. Looking back has helped me to see how far my family and I have come, how far humans and non-humans have come, existing side by side and making life, and what it today, possible for one another. The past has made me the reflective, thoughtful, and spiritual person that I like to believe I have grown to be. The past has brought out the wildness around me.

Deity or Gecko?

Play the video below to watch how a Mediterranean house gecko catches its prey!

Works Cited

- Bartelt, Amber. “HEMIDACTYLUS TURCICUS MEDITERRANEAN HOUSE GECKO.” Texas Invasives. Texasinvasives.org, 25 Aug. 2014. Web. 15 Nov. 2014. <http://www.texasinvasives.org/animal_database/detail.php?symbol=17>.

- Bauer, Aaron M. Geckos: The Animal Answer Guide. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2013. Print.

- Deming, Alison. Zoologies: On Animals and the Human Spirit. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2014. Print.

- Darwin, Charles. The Descent of Man. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton UP, 1981. Print.

- “Gecko or Mo’o.” Hawaiian Life. HawaiianLife.com, 15 Apr. 2010. Web. 15 Nov. 2014.

- Haupt, Lyanda Lynn. The Urban Bestiary: Encountering the Everyday Wild. New York: Little, Brown, 2013. Print.

- Johnsen, Keith. “Reptilia.” Hello Poetry. Hello Poetry, 6 Mar. 15 Nov 2014.

- Kolbert, Elizabeth. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. New York: Henry Holt, 2014. Print.

- Lake-Thom, Bobby. “Reptile and Snake Signs and Omens.” Spirits of the Earth: A Guide to Native American Nature Symbols, Stories, and Ceremonies. New York: Penguin Group, 1997. Print.

- “Mediterranean House Gecko (Hemidactylus Turcicus).” Encyclopedia of Life. Encyclopedia of Life. Web. 16 Nov. 2014. <http://eol.org/pages/456655/overview>.