“What are the novel implications of the Anthropocene? For a start, it forces us to rethink our usual temporal and spatial scales. It pushes us to think about the evolution of our planet back into the deep past and forward into the imagined future.” In the third blog post in the HfE Observatories blog series, Professor Iain McCalman asks what are the novel implications of the Anthropocene?

In 1957 the popular naturalist Bill McKibben wrote that, once we humans were tossed around by the forces of nature; now we are those forces. But it was in 2000 that the term Anthropocene, or Age of Humans, when the atmospheric scientist Paul Crutzen and the biologist Eugene Stoermer gave a formal title to that idea. The Anthropocene, they said, describe a new epoch in which humans have become disruptive bio-physical and geo-physical forces of nature that are leaving enduring marks on our planet.

Geologists set up a working group to investigate whether the Anthropocene era should replace the present 12000-year era of the Holocene when major human civilisations were established on the earth. To make their case for a change, they needed to find a distinctive planetary-wide trace that would still be detectable hundreds of thousands of years in the future. Potential candidates included the massive movement of species and ecosystems across the earth and the equally massive scarring of the planet’s surface by human activity. Eventually, however, they decided that the radionuclides created by atomic bomb explosions in the 1940s were the most compelling signature of this new epoch.

The geologists are still debating this question, but in the meantime, the spirit of the Anthropocene has already skipped out of the lamp. Crutzen himself points out that the Anthropocene has also become a potent metaphor and idea that is now being widely adopted within the humanities, arts and social sciences to evoke a radical new paradigm of human and non-human life on our planet, and a dramatic new way of thinking about our relationships with nature.

What are the novel implications of the Anthropocene? For a start, it forces us to rethink our usual temporal and spatial scales. It pushes us to think about the evolution of our planet back into the deep past and forward into the imagined future. Spatially we move beyond neighbourhoods, regions, nation states and hemispheres to think on a planetary scale, and yet at the same time, the Anthropocene forces us to recognise the most micro-organic levels. We now know that individual human and animal survivals also depend on their relationships with hundreds of miniscule internal bacteria and viruses.

The Anthropocene also leads us to breach traditional disciplinary divides. The famous paleo-biologist Professor Jan Zalasiewicz of the University of Leicester now also utilises science fiction in his work by collaborating with artists to imagine and model the kinds of future fossils our civilisation will leave behind for geologists to discover thousands of years from now. What will they make of a planet filled with fossils of Kentucky fried chicken bones, iPhones, ball-point pens, and plastic-ingested birds?

Such collaborations also reveal how the Anthropocene is breaking down our highly specialised and isolated systems of knowledge. The complexity and urgency of Anthropocene challenges demand that we work and collaborate across the full spectrum of disciplinary fields if we are to understand, mitigate, adapt and survive these unprecedented challenges. This includes recognising our inextricable entanglement with non-human animals and ecosystems.

Yet thinking of ourselves as a planetary species can also be misleading if it means overlooking the monstrous inequalities that exist within the world’s societies. Not all peoples, are equally responsible for the creation of climate-change impacts or equally vulnerable to their hurts. Those who have contributed least to Anthropocene catastrophes such as intensified floods, fires, droughts, cyclones, and warming oceans are being the hardest hit. The rich can insulate themselves; while the poor bear the brunt.

The idea of the Anthropocene also presents conflicting implications about the extent to which we should interfere with nature. We know that our hubristic interventions have caused or intensified most of today’s environmental disasters. Many argue, therefore, that we should cease all such interfering and confine ourselves to conserving and protecting nature so that it can resume its unhindered operations. Unless we drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions, they argue, we will be faced with catastrophic or even apocalyptic consequences, a prospect that fills many of us with feelings of fatalism or despair.

Others argue, however, that we have already so interfered with our planet that there is already no such thing as wild nature left. They believe that we must therefore recognise that pristine nature can never be recovered. Instead, we should use our bio-physical powers to create a ‘good’ or at least ‘survivable’ Anthropocene. From this perspective, we should be using our scientific knowledge to regenerate extinct species or engineer super-resistant reef corals. Such actions, they contend, also have the virtue of inspiring active hope rather than passive despondency.

Either way, we believe that everyday objects can be used to inspire thought and feeling about the Anthropocene. Because they are part of history’s archive and fiction’s imaginary, they can bear witness to both the deep past and the distant future. Neil McGregor in his bestselling book argues that objects ‘speak to whole societies and complex processes rather than individual events.’ They are versatile, multifaceted and can offer clues to intertwined human and natural histories.

Everyday objects also have the power to bridge spaces and join disparate times. They can evoke past, present and future and they can bridge both the global and the local. Objects contain multiple perspectives and stories. We can view them in a literal, material and functional ways or as symbols and allegories. They can generate an almost limitless range of emotions: wonder, beauty, terror, awe, amusement fear, loss, misery, joy, hope, pain, hubris and humility. They have the power to reach diverse publics — young and old, women and men, rich and poor, animals and humans. Above all, objects can move us to think in new ways about what it means to live in the Age of the Anthropocene.

Our consortium of Humanities for the Environment Observatories, which already spans most of our planet’s continents and marine regions, can and does provide us with a superb sounding board for exchanging information and for comparing national and regional Anthropocene effects and implications. Even though each Observatory focuses on relevant local or regional themes, we also meet, think, and debate as a planetary collective in a different location once a year; and we also connect more continuously via our websites. We thus urge and encourage individuals associated with our diverse international network to link with each other and with other individuals and organizations through producing and discussing short, informal, blogs.

This blog post is a summarised version of a paper presented by Iain McCalman, for ‘Making Futures: A Slam Event’ hosted by the Anthropocene Campus and Museums Victoria on September 5, 2018.

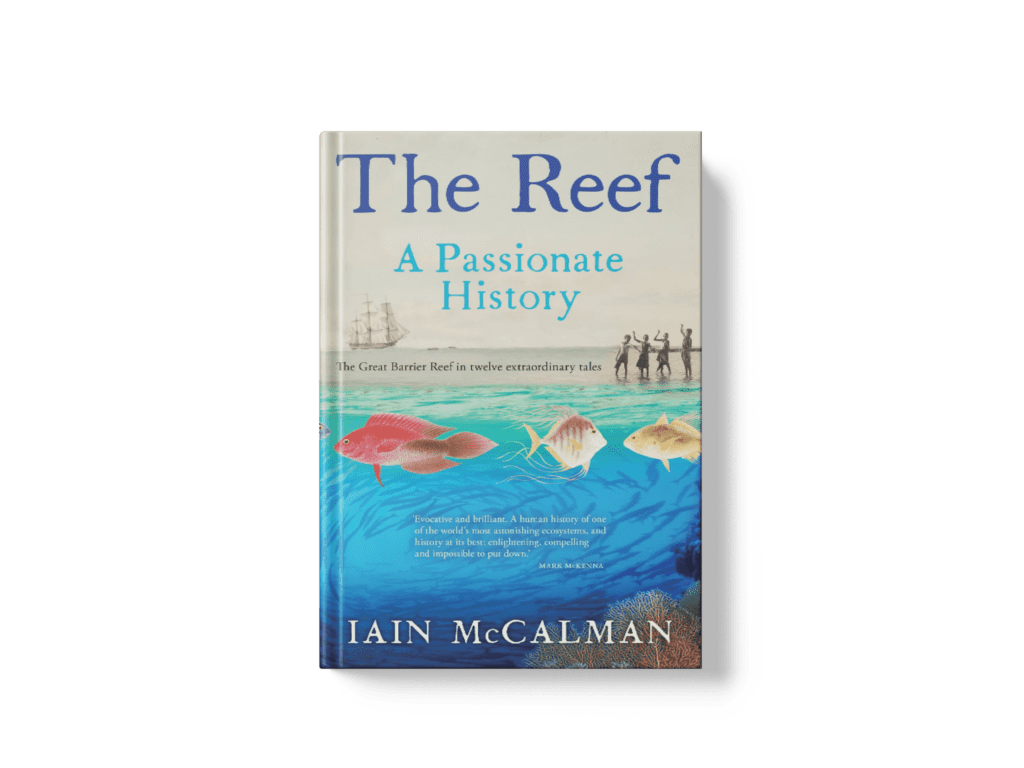

Iain McCalman is currently a Research Professor of History at the University of Sydney and Co-Director of the Sydney Environment Institute. Over his long academic career, Iain has established a national and international reputation as a historian of science, culture and the environment whose work has influenced university scholars and students, government policy makers and broad general publics around the world. He is the author of The Reef —A Passionate History. The Great Barrier Reef from Captain Cook to Climate Change (2014). In 2007 Iain was awarded the Officer of the Order of Australia for Services to History and the Humanities. He is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia, and the Australian Academy of the Humanities and the Royal Society of New South Wales.