Pigeons and doves are the common names given to a number of birds in the family Columbidae. Pigeons are usually larger members of the family while smaller species tend to be called doves. There are over 250 known species of Columbidae worldwide, with the majority found in Southeast Asia, Australia, and on islands in the West Pacific. There are around 175 species of true pigeons, of the subfamily Columbinae, and it is this subfaily to which the genus Columba belongs[i]. The Columba livia, also known as the rock dove, the city pigeon, the dovecote pigeon, or the feral pigeon, is the bird that is most often being referred to when people think of a pigeon; the exception is its white color morph, which is almost always referred to as a dove (e.g. the “dove of peace”)[ii]. I will examine both pigeons and doves in this piece due to the flexibility of the two names in common speech. Throughout this piece, though, the words “pigeon” or “rock dove” will be used to refer only to the Columba livia . The word “dove” will be used in cases where the exact species of the bird in question is unclear, when birds are labeled as a specific kind of dove, such as turtledoves (a common name for a number of birds of the genus Streptopelia in the family Columbidae), or it will be used for birds which, in the sourced documents, are called doves.

Wings brush the sky

And along the steps,

Claws scrabble on the sidewalk

As shimmering heads–

Spotted speckled black white brown–

Bob and coo and puff.

A child’s first sight

Of the wild

A bright orange eye

Starring

Before the car comes and chases

It away.

-E. M. Barton

I remember the Plaza de la Virgin, in Valencia, being completely full of pigeons. White pigeons, grey pigeons, brown pigeons, spotted pigeons, and every color in between. They had no fear. People would walk through the square and the pigeons would scatter, heads bobbing at the same pace that they scrabbled out of the way. But they never panicked. They just shifted, fluttered, and returned to their business of begging for scraps and enjoying the warm sun of the Spanish Mediterranean . Back then, there was a little old woman, a little ragged, drab and brown who sat on the steps and sold birdseed–I wonder now if she was one of the Roma people who gathered in the city, shunned, but resilient and ever-innovative in the arts of survival. Sitting at the helado shop that fronted onto the plaza opposite the Basilica, people watched other people and people watched pigeons; they sipped cortados and licked away at their gelato.

I’m sure they must have watched us, as well. We spoke no Spanish and our clothes were slightly off, with an air of not-Spanish about them. And although blonde hair is not unheard of in Valencia, the people there tend more often to be small, dark-haired and olive-skinned; the traces of Al-Andalus linger in their dominant phenotypes. My brother and I are both fair: progeny of a tall, pale and ruddy-faced family, all with blonde hair (now golden brown with age), we look as Northernly as they come. Paired with the sounds we made and our not-quite-right clothing I think we must have been noticeable foreign. This even after summers spent traipsing about olive groves, through the winding streets of Spanish-Arabic towns, and strolling along Valencia’s sidewalks and beaches, letting the sun tan us light brown and paint gold and copper streaks in our hair. Although we lived in the sun-soaked Sonoran Desert most of the year, the punishing heat meant that we spent more time indoors than out and stayed fairly pasty; beneath the Mediterranean light we squinted a lot and we were thankful for the chilled interiors of stone-walled castles and dim cathedrals.

My parents are archeologists and they always took us with them out into the field. One of my father’s main projects was based in the Mediterranean and thus a fair amount of my childhood was spent exploring the cities, towns, and countryside of southeastern Spain. We spent a special amount of time in olive groves in the province of Valencia, places where people have been farming for centuries and which, therefore, are a gold mine of archeological data. Thus the city we were most familiar with was the city from which the province takes its name: Valencia. It was originally a Roman city, called Valentia[i], and was conquered by the Visigoths in 413 CE. In 714 CE the armies of the quickly expanding Islamic armies claimed it, remaking it into the Emirate of Balansiyyà (or Balansiya) in 1021 CE. In 1094 it was again conquered, this time by the famed Castillian knight, El Cid. After his death, the city was retaken by Islamic forces and was held by them until 1238 when it was conquered by the Christian army of James I of Aragon. The Kingdom of Aragon was united with the Kingdom of Castile in 1479 when King Ferdinand wed Queen Isabella; this created, more or less, the geography of Spain as it is known today[ii] [iii].

Valencia has remnants of all its different overlords scattered throughout it: Moorish tiles and archways, Roman excavations, the Gothic Silk Exchange, Medieval city gates, Arabic baths, and Renaissance squares, to name just a few. La Plaza de la Virgin has its origins all the way back in the city’s Roman days, when it allegedly was the site of the forum[iv]. For me it has always been “Pigeon Square;” ever since I can remember I have associated it with the great flocks of pigeons that linger around it, within it, and on the towers and parapets of the cathedral and basilica that frame it. As a child, I loved those pigeons as much as the gelato we always bought when we went there (my favorites were stracciatella and turrón).

Once, when I was nine and my brother was thirteen, we went to Pigeon Square with our parents and we each bought a bag of birdseed from the old woman who sat on the steps. Our parents went to sit and drink coffee, then, while we went about trying to coax the pigeons into our outstretched hands. The sky reflected in their glassy eyes as they watched us with tilted heads, measuring us, judging us–were we friend or foe? Maybe it was the looming presence of the Valencia Cathedral and its famous tower, the Micalet, behind me, with it’s stained glass windows gleaming and the thousand stone eyes of gargoyles and angles, demons and saints, that made those pigeons seems so special. It was not hard to imagine them as angelic avatars, messengers of God that could take my dreams out of my hands and carry them into the sky.

I held out my hands, full of birdseed and waited. They gathered around me, first close by, then right up near my feet. Finally, I got my wish–a patchwork bird fluttered, flapped, and suddenly I felt it’s tiny, sharp claws digging into my wrist; it’s soft feathers brushing up against my skin. The beat of its wings as it tried to balance filled me with exhilaration and its beak against my palm was a validation: I was accepted into the flock.

I remember how their wings felt like a benediction.

Pigeons are one of the few creatures other than ourselves that can be considered truly urban. They have lived with us for so long–it has been suggested that they were one of the first, of not the first, domesticated animals[v]–that they seem to be more native to our “unnatural” city than to any other environment. That’s a condition that can be applied to few animals and maybe that’s the reason that we have long made a sharp distinction between the city, that which is human, and nature, that which is wild or non-human. But maybe it’s not our cities that are unnatural but our separation of “human” and “natural.” The pigeon for one, simply through its long-term coexistence with our cities and us, brings into question the idea that the human world and the natural world are actually separate entities.

A famous quote from Henry David Thoreau’s essay, “Walking,”[vi] that is frequently misquoted is a good way to think about the potential fallacy in our current human-nature relationship. The misquote is:

“I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wilderness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil,”

But the full and correctly quoted line is:

“I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil,—to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society.”

Thoreau is speaking about wildness, not wilderness, yet it is the wilderness that we so often concern ourselves with. The Out There and Far Away that is Untouched by Man. But wildness, does that necessarily exist apart from us? Or are humans “an inhabitant,” a “part and parcel of Nature,” rather than part of a separate human society? The pigeon, and many other species (including humans), can be wild in their behavior yet exist in the urban environment, the greatest unwilderness there is. But maybe our unwilderness is actually quite suffused with wildness if we only know what to look for. Afterall, as a child in cathedral’s shadow–a great monument of men and their God–it was my faith that in the Wild, that it would recognize me for a kindred spirit, that kept me waiting, hands outstretched, for the birds to come to me. And come they did. Was I Wild as I liked to believe? Were the pigeons Tame? We both existed in and relied upon the urban unwilderness, yet we both came to each other in perfect freedom; maybe we were each a little of both, parts and parcels of Nature, as Thoreau writes, and also of society.

Lyanda Lynn Harp touches on this idea when she proposes a “new nature” in her book, The Urban Bestiary:

“We inhabit what I call a new nature, where the romantic vision of nature as separate from human activity must be replaced by the realistic sense that all of nature, no matter how remote, is affected by what we do and how we live.”[vii]

This idea meshes well with Thoreau’s use of wildness. Both terms pave the way for a new way of looking at nature, one that allows the weedy species –fast breeding species that tend to thrive in the wake of humanity and other calamities, such as rats, cockroaches, and the eponymous pigeon–to be looked upon as fellow inhabitants of a new nature, a nature that exists and all around us, and within us, rather than only in fenced in preserves and parks or far off in our most ancient imaginings. If we are to improve our relationship with the natural world, this is where we need to start–with weedy, overlooked species that we consistently fail to incorporate into our conception of nature, despite the fact that of all of the creatures in the world it is these species that are more similar to us than any other. By understanding them as beings with their own lives, but also as beings with their lives intertwined with ours, we can begin to see ourselves as part of a new ecological web where human and animal, city and nature, are all bound up together.

The Micalet and the Valencia Cathedral have a long history. The cathedral was consecrated as the Cathedral of Saint Mary in the 13th century. Before that it had been a mosque, part of the legacy of the Muslim state, Al-Andalus. And before that it had been a Visigothic church, the only vestiges of which are in the apse, the baptistery, and a chapel crypt[viii]. The bell tower, Micalet in Valenciano, Miguelete in Castellano, was started in 1381 and finished in 1425[ix].

It is a soaring, octagonal tower with gargoyles grinning down from its eight corners and intricately carved, pointed arch windows at the top, below the bell house. From the very peak, above the bells, a thin cross pierces the blue, blue Mediterranean sky: a monument to conquest and human invasion as much as it is to God.

Despite how well they fit in with the bells and gargoyles of the Micalet, pigeons didn’t originate among towers and churchbells. They came from the arid regions of the eastern Mediterranean area; fossils of pigeons, or rock doves as they are also called, at least 300,000 years old have been found in Jordan and on the Palestinian coast. Although it is unknown when humans actually came into contact with them it’s thought that pigeons were one of the first animals to be domesticated[x]; they have coexisted with humans for thousands of years. Mentions of them are found in cuneiform scripts from ancient Mesopotamia and also in Akkadian psalms dating from 2,300 B.C.E.

The modern day pigeon seen on the street are actually the feral descendants of domesticated versions of these ancient birds . There are at least two hypotheses for how the domestication occurred: either when hunters began trapping and then raising of young pigeons to reproductive age, or when the birds began to naturally colonize early cities and so came within easy reach of humans. The Egyptians raised pigeons in dovecotes and used all parts of the bird, from its droppings (for fertilizer) to its meat. Pigeons were also raised in Rome and France from early on, and much of Europe is known to have a history of using dovecotes [xi].

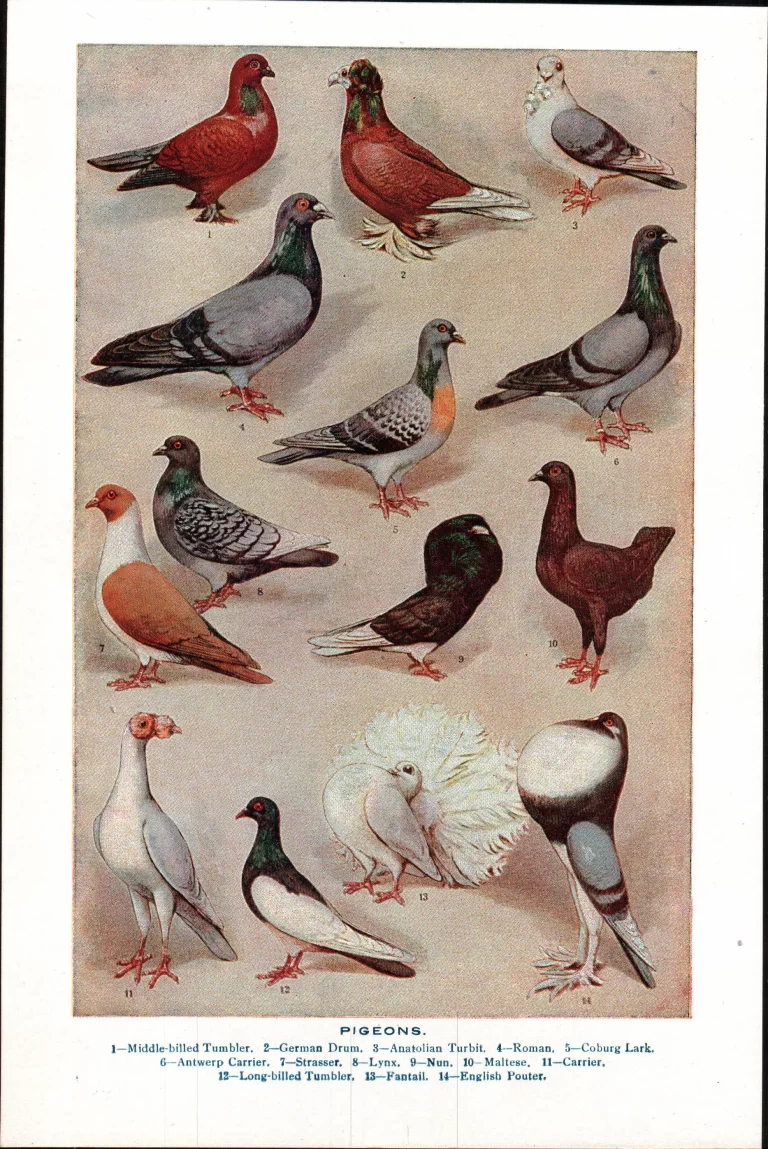

The pigeon was introduced to North America in the 1600s[xii] and can now be found all across the continent. There are currently at least 200 named domestic strains, and a large variety of colors, feather mutations, and sizes that have been selectively bred for. Darwin was an avid pigeon fancier and his experience with pigeon breeding informed the first part of On the Origin of Species. Pigeons seen in the city are usually a mix of domestic strains, but all can be traced back to the Old World rock dove[xiii].

All this is to say that the pigeon, whatever peoples’ personal feelings about them are, have existed side-by-side with humans for a very long time. Therefore it’s no wonder that they have such a complicated relationship with their human neighbors: familiarity breeds contempt. There are numerous pigeon extermination and control companies that pop up in ads when you Google, “pigeon.” And when walking through any city you are bound to see a number of buildings with their ledges covered by plastic spikes to keep pigeons from roosting there. But doing anything more than deterring the birds can get controversial very fast, as a 1999 Riverfront Times article by Jeanette Batz noted when it covered a mass poisoning of pigeons in a St. Louis shopping plaza[xiv]. Although they are, as Batz writes, “birds everybody loves to hate,” having such a long, shared history has also created a degree of affection, or at least a sense of neighborliness. No matter how obnoxious Mr. Next Door is, you wouldn’t poison his morning coffee, right? This affection, connection, or something like it, which people have with pigeons is revealed in their continuous and widespread presence in folklore, cultural traditions, and religions throughout the world.

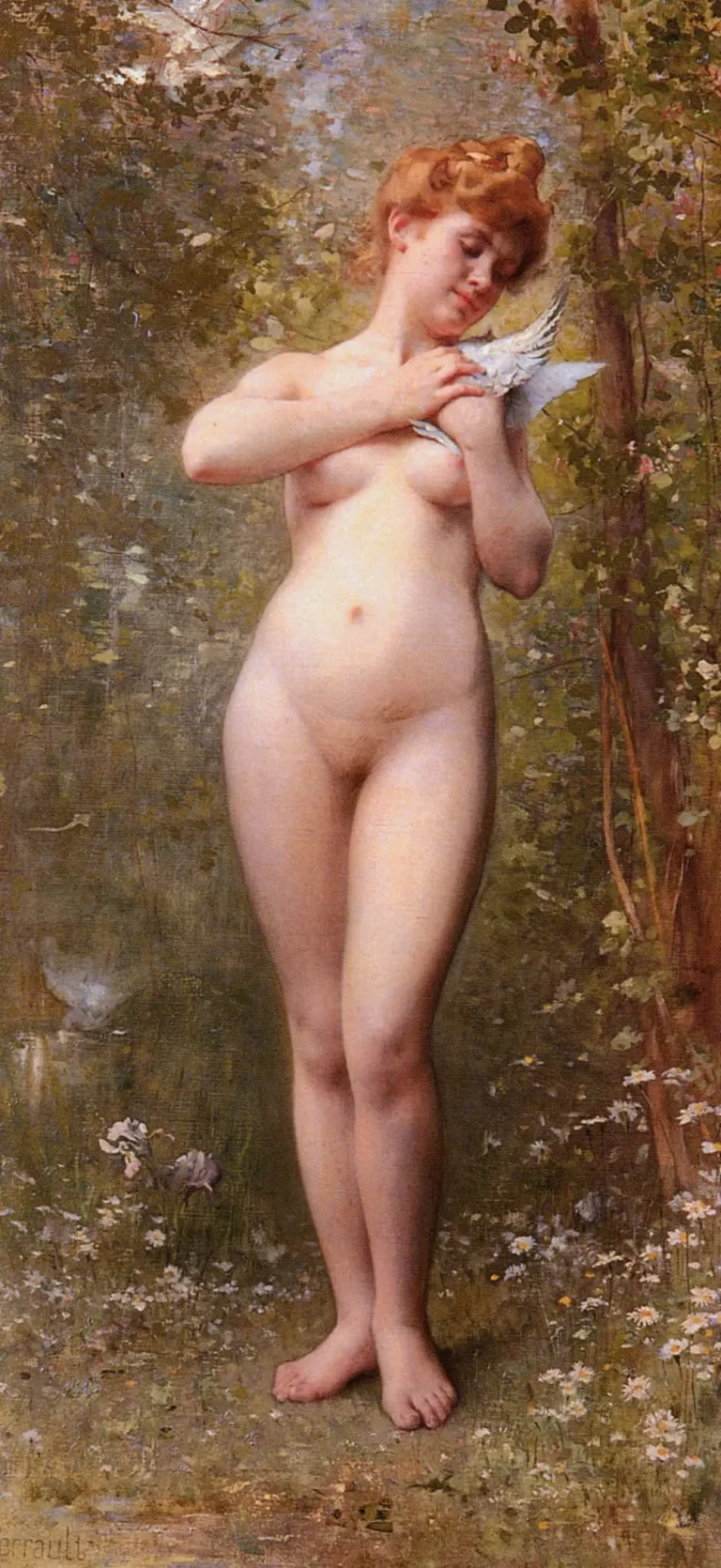

From antiquity, pigeons have been associated with the Divine. They, or their numerous relatives, have been considered sacred or magical to some degree almost everywhere they are known. Often they symbolize the soul or are thought of as messengers between God and humanity. Peace, innocence, gentleness, timidity, and chastity have all been embodied in the pigeon’s rounded form[xv], though they have also been associated with fertility and love Goddesses, especially in more ancient traditions. In Mesopotamia, the fertility goddess Ishtar favored them[xvi], and the Greek Aphrodite, goddess of love, lust, and fertility, was often portrayed riding in a chariot pulled by doves[xvii].

The tradition that doves and pigeons are most powerfully associated with in modern times, though, is that of Christianity. In my own church, long royal purple banners with white doves emblazoned across their fronts hang from the walls during holidays and I have seen them glowing from stained glass windows in numerous others. The story of Noah’s dove is one of the most well-known in the bird’s repertoire; the dove is “perhaps the most Christian of animal symbols,” according to the Chaucer Encyclopedia[xviii]. In the world of Chaucer, at least, it even beats out the lamb.

Geoffrey Chaucer was born around 1343 and wrote during the late 1300s. His stories are telling of the culture in which he lived and are also excellent examples of caricature and symbolism. And although he lived in a time where doves were highly associated with Christianity, in A Parliament of Fowls he used them for their other most well-known association–love and marital devotion. More specifically, he used them to argue for the merits of courtly love, a rather odd but exceedingly popular phenomenon in Chaucer’s time. Courtly love centered on the unattainable: a man, usually a knight, pined after a woman, usually a married one. In best-case scenarios the woman is unmarried and delicately accepts the knights overtures; in worst case she is married and rejects him, at which time he is utterly ruined by the pain of his love. Most often, the woman is married and allows the knight to become platonically devoted to her, at which point the knight serves her and is most worshipful[xix]. The key element is the devotion, as illustrated by the turtledove:

“No, God forbid that a lover should change his mind!” The turtledove said, and then blushed deeply for shame, “Even if his lady should always remain a stranger to him, Still let him serve her forever, until the day he dies. Therefore, I cannot agree with the Goose’s advice; For, although my lady might be dead, I could not love another; I will be hers until death finally takes me.” (Parliament of Fowls, 582–88)

Doves and pigeons mate for life. Exceptionally devoted, if one mate dies before the other the remaining is slow to choose another mate. It’s easy to see how this behavior could link the bird to ideals of chastity, love, and marital devotion, all of which were important elements of Medieval relationships. This association likely lead to one of the many pigeon traditions: releasing doves at a wedding (often, though the birds released are called doves, they are exactly the same as street pigeons except that they have been selectively bred to be white).

Although the Medieval lore likely derived from the dove’s devotion to its mate it also shows how animals can be a mirror for human feelings. In observing the dove’s devotion, Medieval writers perhaps saw elements of the hopeless devotion of “courtly love;” the bird acts as a mirror for humanity even as it acts as a window into nature. Many animals carry as many, or more, symbolical associations for the human cultures they interact with and similarly end up acting as “lessons” for human behavior more than creatures in their own right. The English language is filled with animal metaphors and stories that exemplify the way animals act as human avatars:

Loyal as a dog

A dog in the manger

Calling a pacifist a “dove”

Dirty rat

Sly as a fox

Being catty

Strong as an ox

These are fairly superficial examples, but all show how humans mentally change animals into creatures that are, essentially, an alternate form of human that, because it is not actually human can be a convenient scapegoat for humanities many foibles. Lessons rather than beings.

The Medieval lore associated with doves and pigeons clearly shows the Christian connections they are still famous for. Still, there was a fair amount of lore left-over from the birds pagan days. As often happens when a new religion or culture moves into an area, bits and pieces of the old survived. Doves retained their association with love, for instance, as is seen in Chaucer’s work, and they also retained their association with peace and gentleness. In her book, Zoologies, Hawthorne Deming copies an excerpt from the Aberdeen Bestiary, a work of Medieval England, which shows how the bird manifested more broadly in Medieval minds.

“The dove, with its silver-colored feathers, signifies every faithful and pure soul, renowned for the high esteem accorded its virtues. The dove gathers as many grains of seed for food as the soul does examples of righteous men as models of virtuous conduct. The dove has two eyes, right and left, signifying, that is, memory and intelligence. With one it foresees things to come; with the other it weeps over what has been.”

According to Hawthorne Deming, the Aberdeen Bestiary is not so much a work of natural history as a theology, “glorifying the Christian wisdom tradition.” In it, animals were described but also used to impart moral lessons. The book’s fantastic illustrations made it a useful teaching tool even if the students were illiterate. Despite its age, the bestiary’s entries are not so different from how we still see most animals; few people look at a pigeon and think of its biology, or its true behavior. They think instead of all the things a pigeon represents to them and all the things they’ve heard about pigeons from their friends, on the news, or in movies. They might think of city life, filth, commonness, flying rats, peace, love, or the Holy Ghost. In other words, people think about animals, and relate to them, more like a medieval bestiary does than does a biology textbook–on an emotional, moral, and spiritual level that can, at times, overwhelm the pigeon’s reality as an actual, living creature who affects and is affected by us.

Nowadays humans often treat animals as “little humans” when we encounter them as pets, or even in the wild, yet at the same we attempt to separate “human” and “nature” –we fail to acknowledge our own animal nature even as we see human natures in animals. It is strange that we seek to paste humanness onto animals when, according to Jungian analyst Neil Russack, “animals are always true to themselves. They can never be anything else. In this sense they are religious. They always act out of their deepest self.” [xx] Shouldn’t it be animalness that informs humans, then? We who are always seeking our deepest self, our Truth, our religion; shouldn’t we look at animals as they are, “true to themselves,” if we want to learn a real lesson? Unless we admit that we, too, are animals. Like the dog, we can be both vicious and sweet; like the pigeon, we gather in great numbers, spread across the Earth, and turn our homes into trash heaps. Like nature, we are beautiful and terrible all at once.

Whether or not the mirror we see in an animal’s eyes is an accurate representation of the beast itself, the fact that we have consistently seen ourselves reflected in the wild is a key hint that we are not as separate as we like to think ourselves. The behaviors that we like to brush off as “beastly” faults, as an unnatural state of humanity, are no different from the Orca’s love of playing with its food, or the widespread tendency of predators to practice overkill. They are as natural as our intellectual virtues and if we compared ourselves to animals as they are perhaps we would see this. The devotion of the pigeon is as much a part of it as its dirtier habits.

As Hawthorne Deming writes in Zoologies, “animals are a manifestation of the planet’s imaginings.” We are just as much part of the planet’s imagination as the fox, the dove, the rat, and the dog. Not the same, as we sometimes pretend, nor so different in as to be unreachable, but of the same dream.

The white dove’s association with Christianity and its Christian symbolism as a creature of spirituality and peace is still very powerful today, so much so that it has become an internationally recognized symbol of peace: the dove and the olive branch[xxi]. Although the dove was a symbol of peace and gentleness before Christianity, the modern-day symbol derived in a large part from the story of Noah’s ark, one of the Bible’s most well-known stories featuring a dove:

“Also he sent forth a dove from him, to see of the waters were abated from off the face of the ground; But the dove found no rest for the sole of her foot, and she returned unto him into the ark for the waters were on the face of the whole earth: then he put forth his hand, and took her, and pulled her in unto him into the ark. And he stayed yet other seven days; and again he sent forth the dove out of the ark; And the dove came in to him in the evening: and, lo, in her mouth was an olive leaf plucked off: so Noah knew that the waters were abated from off the earth. And he stayed yet other seven days; and sent forth the dove; which returned not again unto him anymore” Genesis 8: 10-12

The dove shows up in other places throughout the Old Testament, too, and is mentioned more than any other bird in the Bible. Both pigeons and turtledoves (mourning doves) are referenced as appropriate sacrifices to God–“a pair of turtledoves or two young pigeons”–and the birds represent freedom, escape from tyranny, harmless, innocence, and meekness[xxii]. All of these are traits that might have appealed to a people whose history and lore is steeped in exile and subjugation, once again revealing the way that our relationships with the animals around us tend to mirror our own emotions.

In the New Testament, the Holy Spirit takes the form of a dove when it appears to Jesus: “And the Holy

Ghost descends in a bodily shape like a dove upon him, and a voice came from heaven, which said, Thou art my beloved son; in thee I am well pleased” Luke 3:22. This is another well-known instance in the dove’s lore and the reason that the white dove is often used to represent the Holy Spirit or Christian spirituality. In Christian art and literature, the dove is also frequently used to represent the Holy Spirit, or sometimes the messenger, during the Annunciation, when Mary was told that she was pregnant with Jesus. Perhaps because of this, the dove has also come to be a symbol of the Virgin Mary[xxiii], thus the bird was once more associated with a female Divine figure as it was in more ancient times.

I’m not sure why the pigeon seems to have a more feminine connotation than a masculine one. Male and female pigeons are the same in appearance and they devote an equal amount of time to their nests. However I usually tend to notice the males more often, since they puff up their throats and strut about trying to impress females. It’s interesting how, despite this prominent masculine behavior, the bird is so often seems to be read as a feminine creature. Perhaps one reason for this is the pigeons’ chick-feeding habits. Notably, pigeons do not feed their young with food brought to the nest. Instead, both male and female pigeons create a milk-like substance in their crop. The milk production is stimulated by the same hormone that stimulates milk-production in female mammals–prolactin[xxiv]. Combined with their non-threatening nature and their ability to provide humans with all manner of necessary goods–meat, eggs, feathers, entertainment, etc–the pigeon’s milk production could have helped place it in the feminine camp.

I never really associated the birds with male or female, though, so maybe the connection isn’t a strong one. What is strong is their enduring curious character and their physical beauty. Everywhere I’ve encountered pigeons (and I’ve seen them in pretty much every city I’ve ever been to) they lend a certain other-worldliness to the cityscape, whether that be a bizarre, sometimes grotesque, sideshow carnival, a pastoral ease, or the soaring majesty of a cathedral.

I think I remember them most as they were in La Plaza de la Virgin because of how beautifully they complimented the old architecture. With their round bodies and earthy colors they often looked like little gargoyles perched on the edges of buildings–concrete angels come to life, a whole flock of the Faithful. All the Christian lore held beneath their feathers seemed to resonate with the chiming of the bells. In Mary Poppins, Julie Andrews manages to elegantly capture the feeling that the birds create as they fly about a cathedral as she sings the song “Feed the Birds.” The woman she sings about is much the same as the little old woman who used to sit on the plaza steps, only my brother and I bought bird feed for pesos instead of tuppence.

Pigeons don’t have quite the same magnificence in Tempe, where I usually live. Here even their typical contemporary association with gritty urbanity is superseded by the suburban environment they find themselves in–like the people, suburban pigeons seem softer, slower, and more appreciative of grassy lawns than concrete towers. In their grassy parks and yards, the pigeons look more like fat, cartoon cows grazing across the lawn and surrounded by their smaller cousins, the Inca dove and the mourning dove, little sheep bouncing through the cow herd. The sparrows become miniature chickens pecking at what’s left. I can almost here the theme song for “Harvest Moon” playing when I see them all fluttering out to pasture. Gargoyles and angels don’t have much place here; the birds reflect the city life around them, whether that be ancient bell towers or suburban sprawl and Hawaiian shirts. It’s not just humans that change their behavior to match their location.

Even at their most clownish and unremarkable, though, pigeons are quite lovely. They’re native coloring is grey, with black bands on the wings and tail, and iridescent throat feathers[xxv]. Because of extensive mixing of domestic strains, though, the pigeons seen on the streets can come in a fantastic array of colors and patterns, from brown to black to white, and sporting spots, speckles, checks, bands, dots or patches. Highly social creatures, pigeons often gather in large flocks. This can add to their majesty, especially when they take off in great waves of wings and feathers. Their flocks are not as large as the extinct passenger pigeon’s once were though, at least I have never heard tell of a pigeon flock “blotting out the sun” as some say the passenger pigeon once did. This is lucky, perhaps, as one of the main reasons that pigeons and people come into conflict is over the large amounts of poop that large amounts of pigeons leave behind.

It’s here that you really start to realize how much we take pigeons for granted, or rather, how much we simply fail to take note of their existence as actual beings. Most of us have no clue about the effects pigeons have on our shared urban environment, or how we affect them. Although our knowledge of food webs and ecological relationships of the ocean and the forest are painted across the pages of 9th grade biology textbooks, our own web of interactions is missing. Pigeon poop is a good example of this. Everyone hates pigeon poop (or I assume that to be the case as most people hate excrement of any kind). It’s ugly. Building managers work hard to cover every ledge they own with spikes; some people even resort to laying out poison. In terms of historic conservation, such measures seem less extreme than they otherwise might: pigeon poop can have damaging effects on limestone, which is what many old cathedrals and historic buildings are made of[xxvi]. Thus all those beautiful pigeons that Mary Poppins sings about, the ones that lend St. Paul’s cathedral and extra air of holiness, are helping to slowly eat away at it–the small, innocuous pigeon has the power to destroy some of the greatest works of Man without even trying. Even deep within our urban strongholds the forces of Nature ultimately hold sway and for all our efforts we are not held separate from decay, the fate of all things that create and live.

But few people realize this.

No matter how many “Don’t feed the pigeons” signs or ordinances are put in place people still feed them. The pigeons still come. People hate pigeon poop, but feeding pigeons will obviously result in more pigeons and more poop. And even when people don’t directly feed them they don’t make any effort to reduce the trash and leftovers that pigeons love to eat. Of course, some people like the pigeons enough to not care about the pigeon poop. Many people get great joy from their interactions with pigeons[xxvii] and, as Mary Poppins sings, like to express their love of nature by “caring” for the pigeons. Or maybe they’re just lonely. For all their people cities aren’t always the most welcoming environments, and the loneliest feelings come when there are people all around. The attentive, bright stare of a hopeful pigeon must seem a blessing to those who struggle with such feelings. Still, there is a disconnect between the effects pigeons can have on the urban environment and how people relate to them; pigeons are so much a part of the urban scenery (back drops in every movie) that we fail to see them as a part of a larger ecological web that includes us and our habitat, in this case buildings and monuments.

Pigeons also reuse their nests again and again never cleaning them. This results in a sturdy mass of guano and other organic build-up that anchors the nest[xxviii]. Not only is this unsightly and potentially smelly, but when there are large amounts of pigeons roosting together, it can lead to extremely filthy conditions where parasites, disease, and other vermin thrive. This all sheds a less pleasant light on the pigeons of Valencia who like to perch atop the ancient statuary and flap about the squares in such great numbers.

But where did all the pigeons come from? Answering that question once again reveals how disconnected we are from the actions and reactions that define an ecosystem and its inhabitants. Not only do we fail to understand our own role in turning the pigeon into something that we are in conflict with, but we fail to see how similar relations occur amongst members of our own species. People from all over are drawn to the city in hopes of a better life, of food and home and work. The poorest are forced into tight, dirty accommodations, if they get any accommodations at all. They live off scraps, or what we deign to feed them. Often, when we do feed them, it is to make ourselves feel better more than as a truly altruistic act. Like the pigeon, we foul our own nests. But at least the pigeon does so with purpose and intention.

After World War II, the pigeon had its own “baby boom” and the population exploded. Part of this was because of escaped domestic pigeons swelling the already established feral and semi-feral populations. Another reason was because after the War, food became much cheaper and more plentiful. The result was a lot more waste, also known as pigeon food. With so much easy to get food around, pigeons could breed throughout the year. The population also benefited from the reduction of their natural predators, mostly raptors such as the peregrine falcon, due to hunting, disease and poisoning (through pesticides like DDT)[xxix], and their lesser ability to adapt to the an urban environment. It’s due to their current overpopulation that many pigeons live in such squalor, becoming vectors for diseases that harm them and that can sometimes transfer to the humans around them. Such living conditions is probably where the idea of pigeons as “rats with wings” came about, as well as the common perception of them as dirty.

If this is true, that the reason pigeons have a bad reputation is due to how they have adapted to the urban environment, then is our city really unnatural afterall? Is it leading birds, divine for much of their existence, down a path of squalor and illness? Or maybe it only seems unnatural because we aren’t looking at the ecological connections that bind us in a food and population web with our feathered neighbors. After all, the exact same argument could be made for people: the overcrowded conditions of the city, or anywhere, can easily lead to slum conditions where hygiene is poor and disease runs rampant. And overpopulation is caused by shifts in food and labor systems that cause migration to urban areas; it’s caused by a lack of birth control, by poor social policies, by misunderstood relationships. Like the people, the pigeons were never actually holy; they were never anything other than pigeons who cared nothing for whether humans called them messengers of God or messengers of death and pestilence. They simply keep on trying to do what all life tries to do, what all the people flooding into the city try to do: adapt. The only difference is that unlike some species, pigeons are very good at doing it.

Seeing urban creatures as filthy and ragged can be an uncomfortable reminder of how many people live in similar conditions. Even in a developed nation, such as the United States, there are vast amounts of poverty. Homeless people sit on the streets of my own city, sometimes asking for money, often asking for nothing at all. Like the pigeons, they simply exist on the street, becoming a part of the urban landscape. We forget about them. Overlook them. We let the dirty, poverty-stricken underbelly of our cities grow and fester, producing children locked into cycles of poverty. Our nest is far dirtier than any pigeons. And when we try to fix it, our efforts are often about as effective as trying to get rid of a flock of pigeons roosting on a cathedrals towers. How many humans have been victims of slum clearing policies or anti-squatter campaigns where their homes are destroyed in the pursuit of urban beautification or disease control?

Slum clearance policies generate a large amount of debate and can manifest in multiple ways. Sometimes people are fairly compensated and/or relocated by the government, and slum clearances can pave the way for economic revitalization. This is not always the case, though, and many slum clearance policies have been accused of being racist, classist, or discriminatory in some way, or else just badly planned. One notable example in the U.S. is how Title 1 of the 1949 Housing Act was implemented in New York City. Although the Act had been proposed with good intentions, the New York City Slum Clearance Committee that enacted it ended up destroying poor neighborhoods and displacing thousands of the poor and having an especially harmful affect on black New Yorkers. Few of the displaced were ever re-housed and those who were relocated were sent to massive, bleak housing projects that did little to improve their living conditions[xxx].

From acting as symbols and scapegoats for a variety of human emotions and foibles to representing religions, to being the everyman’s food, pigeons have been just about everything to humans at one time or another. Perhaps this even contributed to their association with divinity: anything that humans could need the pigeon could provide. And perhaps most famously, they could always find their way home, carrying the messages of their owners along with them.

The pigeon’s navigational ability is not fully understood, but it is truly remarkable. Pigeons are able to find their way home when released from distant locations, even if the location they are released from is unknown. It is suspected that both an internal mapping ability and an internal compass ability are used by the birds[xxxi]. Some hypotheses on how they do this are that they navigate using the earth’s magnetic fields, by using sound or smell, or by the position of the sun[xxxii]. None of these theories seem to offer a complete explanation for how the birds navigate so well, though.

Before the Internet, pigeons were one of the fastest ways to send a messages–of war and peace, symbols of the soul, portents of death, living compasses, saviors, spies, scientific subjects–and their homing instinct has been taken advantage of since ancient times. Pigeons trained specifically to use this ability are called “homing pigeons,” but these are not a different species from the domestic rock pigeons. In ancient Mesopotamia, sailors would release pigeons from their ships because the pigeons would instinctively find land and could thereby be used as “living compasses.” It was this use that is mentioned in the Bible, when Noah releases the dove in order to see if the flood had gone down enough for the Ark to land[xxxiii]. The ancient Greeks and Persians used pigeons as messengers, and later in Europe the birds were considered a symbol of power and prestige and so keeping them was the province of nobility. It was in War, however, that the homing ability of the pigeon has become most renowned.

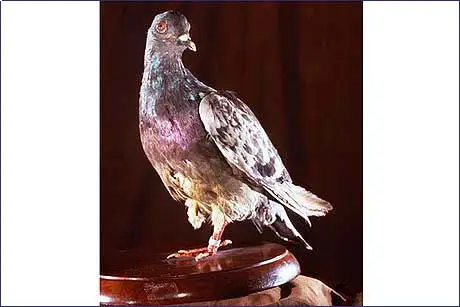

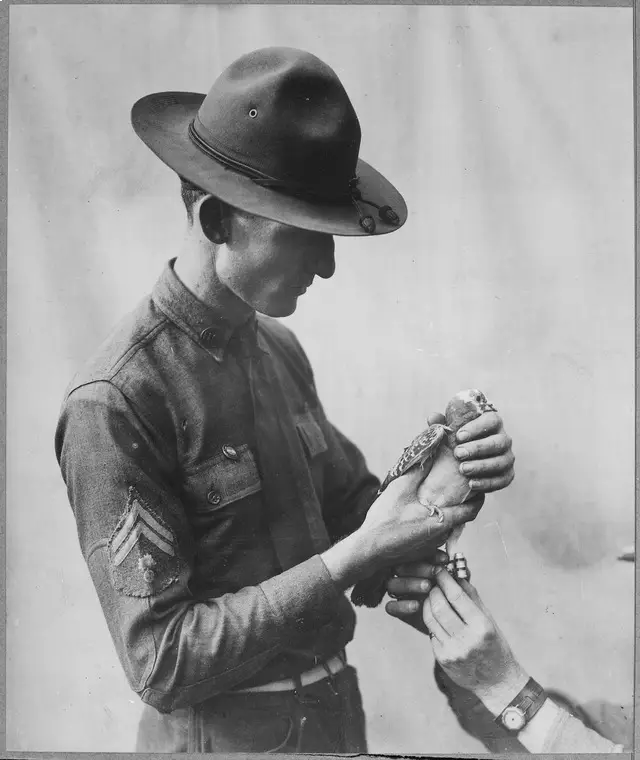

In World War I, the European armies all used homing pigeons; they were the early twentieth century version of modern radio communications and were less vulnerable than the telegraph system. Over half a million birds were used throughout the war, with a 95 percent success rate in delivering messages[xxxiv]. One of the most famous pigeons of World War I was Cher Ami, the pigeon whose message saved the “lost battalion” in France. Cher Ami was heavily wounded but still managed to deliver her message[xxxv]:

“We are along the road parallel to 276.4. Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heaven’s sake, stop it.”[xxxvi]

She saved the lives of 600 soldiers and was later awarded the Croix de Gurre with Palm. Another pigeon from France, called Le Vaillant, received the Ordre de la Nation for its bravery[xxxvii].

Pigeons were also used in World War II, despite the advances in communication technology. The U.S. Army

Pigeon Corp contained 54,000 war pigeons at during the war and had a 90% success rate[xxxviii]. G.I. Joe was a famous WWII pigeon who recieved the Dicken Medal for gallantry. He flew 20 miles in 20 minutes, delivering his message right as the bomber planes set to attack the village of Calvi Vecchia were getting ready to lift off. His speed saved the Italian village and the British troops that occupied it from being destroyed by friendly fire[xxxix].

Pigeons in WWII were particularly useful for communication during radio silence and were also used as spies. Cameras were mounted on the pigeons’ bellies in order to take aerial pictures behind enemy lines[xl]. The people who worked with the pigeons in the army were known as pigeoneers. Often they had been pigeon handlers or fanciers in civilian life[xli]. Alessandro Croseri immortalized these soldiers and their feathered companions in his 2012 documentary, Pigeoneers.

The movie combines interviews and old photographs to follow the story of Col. Clifford Poutre, the Chief Pigeoneer of the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Poutre was one of the leading experts on training pigeons for military service and introduced many innovations in the Pigeon Services, including training technigues that rejected the punishment method. In his career he managed to teach many of his pigeons skills that had never been used before, such as how to return to a mobile loft, how to carry packages and cameras, how to fly at night and for 24 hours without stopping, and even how to carry a canary on their backs. The use of pigeons by the U.S. military was discontinued in 1957[xlii].

Interestingly, ever since I began keeping an eye out for them I’ve noticed there are fewer pigeons in my home city of Tempe than I had thought. Around the university it’s the grackle that seems to fill the role of ubiquitous urban bird. Not to say pigeons aren’t present. They are. I saw several as I was walking back from work the other day, scrappy dark things bobbing about in the grass by the bus stop.

Only two. Nothing like the great flocks I used to see in Valencia. Sometimes I also see them gathering in certain yards in my neighborhood or on the wide, grassy lawns on campus. They don’t seem to like the irrigation floods or the sprinklers like the grackles do, though. I’ve never seen them bathing. Maybe they don’t appreciate getting wet? When it rains, I can see them from my porch (Or maybe I’m seeing ring-neck or mourning doves? It’s hard to tell from a distance.) sitting on the power lines, fluffed up against the damp and looking grumpy. Not that pigeons probably get grumpy, but that’s what they look like.

I think they prefer the Phoenix downtown area to my suburbia. Perhaps because the downtown area actually has skyscrapers that mimic the habitat that the pigeons allegedly came from, oh so long ago–sea cliffs in the eastern Mediterranean region (“Origin and Evolution.”). Of course it could also be that I notice them more in Phoenix because I associate pigeons with big-city skyscrapers. It’s an association that stems from the ubiquitous yet nearly subliminal presence of the pigeon in popular culture: almost any movie that takes place in a (Western) city has at least one pigeon cameo. There even an entire blog, The Pigeon Movie Database, devoted solely to pointing this out. What makes it so interesting is that we are so used to seeing pigeons that we don’t notice them anymore, not like we notice other animals that cross our path. We get ever so excited about deer, hawks, coyotes, but not pigeons. Pigeons might as well be invisible, except when they’re causing problems. But they’re always there. And what would we do if they weren’t?

High-rise office workers see them roosting outside their windows; old men and women find solace feeding them in parks; marriages are sanctioned by them; religion praises them; their intelligence has been verified and studied by numerous scientists; and even when they are hated any attempt to systematically remove them is often met with controversy[xliii]. Whatever anybody’s personal feelings about the pigeon, this bird has become an essential element of human life–they are as native to the urban sphere as people.

Things have changed in Valencia since I was a child.

For the last several years there has been no birdseed seller sitting on the steps in front of the helado shop. San Miguelete requires a fee to enter–no more aimless wondering within its cool musty chambers, watching the candles of the faithful burn in the dimness. The city has been trying to get rid of as many pigeons as possible. They’re more skittish now as a result, taking off in a flurry of whites and splotchy color as skateboarding teenagers screech through the center of the plaza and keeping their distance from the people who walk through the square. There’s no old woman (ragged and poor-looking) selling birdseed on the cathedral steps. The guardia, the Spanish police, must have told her to stop. She and her business were cleared out, but there are still plenty of expensive restaurants around the square whose crumbs and trash give the pigeons all the food they could want. It doesn’t really make sense, but then getting rid of pigeons never seems to be about the pigeons, exactly. If it was, I think people might try harder to do so.

As much as our continual use of animals as metaphors obscures their existence, I can’t help but do the same thing. To describe my changing life, to write about people and life, I talk about pigeons. But I’m not really talking about pigeons, at least not entirely. I don’t actually know much about pigeons as pigeons, only pigeons as they are in relation to people. And this is always the way it is with animals. We’re not really talking about them; we’re talking about us. Saving the pandas, or the wolves, or the tigers, is about saving a memory, a piece of culture that we want our children to see. Animal testing is about making our life better, as rescuing test animals is about making our conscience clearer.

Maybe to avoid this pitfall, I can talk about my relationship with pigeons. I would not run amongst the birds these days, trying to get them to bless me with their wings. Nowadays I’d be worried about all the potential parasites and diseases that a pigeon can carry, and I’m not at all sure I’d be okay with touching one. I grew up. I grew a bit cynical, maybe, and started to lose the ability (the desire?) to see what’s right in front of me. I cannot see pigeons for what they are, anymore, I see them for what people have made them: angels, demons, vectors of disease, heroes, and messengers.

As all things in nature, I follow a pattern that many of my species have followed before me. Children will run through flocks of pigeons to watch them fly up in a great, startled cloud of wing beats and wind. They are still full of wonder and curiosity about the world around them and how they fit into it. They still take the world at face value. Adults will rarely engage in such behavior. They will rarely see the pigeon without their own baggage attached to it. And most of the time, pigeons are just background noise for them. So it is for me. But when I go to Valencia I still think of Pigeon Square and the way air feels when its beaten by a hundred wings. I notice the birds. I think about them. I sit and observe them, and the world too. Restrained, sometimes wary, but always curious. Not unlike the pigeon itself.

This isn’t so surprising when you consider that it is the pigeon, after all, that gives many city-bound humans their first taste of wildness. After cats and dogs, pigeons are one of the non-human creatures a child is most likely to see in the city, and they will see them all throughout their life. Without them the city, somehow, seems a little less. A little lonely. As one of the few animals that seem utterly immune to our destructive domination of the biosphere, the pigeon is of our most dogged reminders, our most ancient messenger, of a world outside of our own; whether that world is Nature, the Divine, or some combination of the two, the pigeon flies between with little effort, alternatively showing us either a mirror or a window to another world. They show humans what it is to fly free, above the rat race and the crowded, sometimes unpleasant, piece of habitat we have created for ourselves. Or maybe, as another species living and dying within our urban sphere yet beyond the control of humans, they simply show is that we have a habitat at all. And if our sprawling, steel and concrete creations, the sometimes apocalyptic landscapes we create, can be considered an ecosystem, then maybe there’s hope for us to find our way to a “new nature”[xliv] after all, one that encompasses both the shared and the separate aspects of human, animal, and all the webs of history, culture, conflict and fellowship that tie us together. In the pigeon, and in all those creatures we consistently overlook, we find ourselves and a wildness all our own. Or we could, if only we would take the time to notice.

“Hope” is the thing with feathers –

That perches in the soul –

And sings the tune without the words –

And never stops – at all –

And sweetest – in the Gale – is heard –

And sore must be the storm –

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm –

I’ve heard it in the chillest land –

And on the strangest Sea –

Yet – never – in Extremity,

It asked a crumb – of me.

-Emily Dickinson

Endnotes

[i] ‘History of Valencia’, Spanish Town Guides: Your Complete Guide to Spain, 2002 <http://www.spanish-town-guides.com/Valencia_History.htm>.

[ii] ‘History of Valencia’.

[iii] ‘Valencia (Spain)’, Encyclopedia Britannica <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/621977/Valencia> [accessed 28 November 2014].

[iv] ‘Plaza de La Virgin’, Valencia City Guide, 2005 <http://www.valencia-cityguide.com/tips/things-to-do/plaza-de-la-virgen.html>.

[v] Daniel Haag-Wackernagel, ‘The Feral Pigeon’, Research Group Integrative Biology <https://anatomie.unibas.ch/IntegrativeBiology/haag/Culture-History-Pigeon/feral-pigeon-haag.html>.

[vi] Henry David Thoreau, ‘Walking’, 1862.

[vii] Lyanda Lynn Haupt, The Urban Bestiary, 1st edn (New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company, 2013).

[viii] ‘Valencia Cathedral: History’, Valencia Cathedral, 2014 <http://www.catedraldevalencia.es/en/historia-de-la-catedral.php>.

[ix] ‘Valencia Cathedral: History’.

[x] Haag-Wackernagel.

[xi] ‘Origin and Evolution’, Natural History Museum <http://www.nhm.ac.uk/nature-online/species-of-the-day/evolution/columba-livia/origin-evolution/index.html>.

[xii] ‘Rock Pigeon’, The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds <http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/rock_pigeon/lifehistory>.

[xiii] ‘Pigeon (bird)’.

[xiv] Jeannette Batz, ‘Pigeons Dropping’, The Riverfront Times, 13 January 1999, section Cover <http://www.urbanwildlifesociety.org/pigeons/PijPsnSt_LouisRivrFrtTimes.htm>.

[xv] Caitlín Matthews and John Matthews, ‘Dove’, The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures (New York, NY: Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc., 2005), pp. 171–72.

[xvi] Donald A. MacKenzie, ‘Chapter XVIII-The Age of Semiramis’, sacred-texts.com, 1915 <http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/mba/mba24.htm>.

[xvii] Matthews and Matthews.

[xviii] Shannon L. Rogers, ‘Dove’, All things Chaucer an encyclopedia of Chaucer’s world (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2007) <https://login.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/login?url=http://literati.credoreference.com/content/title/abcchaucer> [accessed 14 October 2014].

[xix] Rogers.

[xx] Alison Hawthorne Deming, Zoologies, 1st edn (Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2014).

[xxi] Haag-Wackernagel.

[xxii] Matthews and Matthews.

[xxiii] Matthews and Matthews.

[xxiv] ‘Pigeon (bird)’.

[xxv] ‘Rock Pigeon’.

[xxvi] Haag-Wackernagel.

[xxvii] Haag-Wackernagel.

[xxviii] ‘Rock Pigeon’.

[xxix] Haag-Wackernagel.

[xxx] ‘Slum Clearence’, Learning Adventures in Citizenship <http://www.pbs.org/wnet/newyork//laic/episode7/topic3/e7_t3_s2-sc.html>.

[xxxi] ‘Navigation’, The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds, 2007 <http://www.birds.cornell.edu/allaboutbirds/studying/migration/navigation>.

[xxxii] ‘Rock Pigeon’.

[xxxiii] Haag-Wackernagel.

[xxxiv] Jim Greelis, ‘Military’, The American Pigeon Museum <http://www.theamericanpigeonmuseum.org/military-pigeons.html>.

[xxxv] ‘Cher Ami-World War I Carrier Pigeon’, Smithsonian Seriously Amazing <http://www.si.edu/Encyclopedia_SI/nmah/cherami.htm>.

[xxxvi] ‘Letters of Note: FOR HEAVENS SAKE STOP IT’ <http://www.lettersofnote.com/2010/05/for-heavens-sake-stop-it.html> [accessed 21 October 2014].

[xxxvii] Mary Blume, ‘The Hallowed History of the Carrier Pigeon’, The New York Times (New York, NY, 30 January 2004), section Archives <http://www.nytimes.com/2004/01/30/style/30iht-blume_ed3__1.html>.

[xxxviii] Everett B. Miller, ‘Chapter XVIII’, U.S. Army Medical Department: Officec of Medical History <http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwii/vetservicewwii/chapter18.htm>.

[xxxix] Joe Razes, ‘Pigeons of War’, America in WWII, August 2007 <http://www.americainwwii.com/articles/pigeons-of-war/>.

[xl] Greelis.

[xli] Miller.

[xlii] Razes.

[xliii] Batz.

[xliv] Haupt.

For such an innocuous and oft ignored species, the pigeon finds itself in the headlines a fair amount. I’ve collected some of the more eye-catching headlines from the last year to showcase how society at large, or at least the mass media, typically portrays the pigeon.

- A Christmas miracle for ‘Turkey’ the baby pigeon! Little chick survives plummeting from the sky after slipping from the mouth of a …

- Pigeon population — and droppings — increasing in Fairbanks

- Town Pigeon and Country Pigeon

- Pigeon love simulator Hatoful Boyfriend is flying to PS4 and Vita!

- Bird fans in a flap over Redhill’s apparent pigeon exodus

- Planned pigeon shoot attracts protesters, but no shooters

- Homing pigeon dispute has feathers flying

- Pigeon, Man’s Best Friend

- Pigeon Shoots: Pennsylvania’s Secret Shame?

- Livingston weighs solutions to pigeon problem

- The Pigeon Fliers of New York

- Chinese security officials carrying out anal probes on pigeons set to be released as part of National Day celebrations in case …

- China cracks down on speculative carrier pigeon bubble

Bibliography

“Attaching a Message to a Signal Corps Carrier Pigeon, circa 1917-18., 1917 – Ca. 1920.” Wikimedia Commons/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, ca. 1920 1917. Still Picture Records Section, Special Media Archives Services Division (NWCS-S). National Archives and Records Administration. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Attaching_a_message_to_a_Signal_Corps_carrier_pigeon,_circa_1917-18.,_1917_-_ca._1920_-_NARA_-_512434.tif.

Badke, David. “Dove.” The Medieval Bestiary, n.d. http://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast253.htm.

Batz, Jeannette. “Pigeons Dropping.” The Riverfront Times, January 13, 1999, sec. Cover. http://www.urbanwildlifesociety.org/pigeons/PijPsnSt_LouisRivrFrtTimes.htm.

Bazille Perrault, Léon. “Vénus À La Colombe.” http://palgraphicsarea.blogspot.com, 2008. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Perrault_Leon_Jean_Basile_Venus_A_La_Colombe.jpg.

Blume, Mary. “The Hallowed History of the Carrier Pigeon.” The New York Times. January 30, 2004, sec. Archives. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/01/30/style/30iht-blume_ed3__1.html.

“Cher Ami-World War I Carrier Pigeon.” Smithsonian Seriously Amazing, n.d. http://www.si.edu/Encyclopedia_SI/nmah/cherami.htm.

en.wikipedia, United States Signal Corps Original uploader was Brianhe at. English: War Pigeon Cher Ami, April 5, 2010. Transferred from en.wikipedia; transfer was stated to be made by User:kallewirsch. (Original text : United States Signal Corps via Smithsonian Institution, http://historywired.si.edu/enlarge.cfm?ID=522&ShowEnlargement=1). http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cher_Ami.jpg.

Esteban Murillo, Bartolomé. “The Annunciation.” The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH., 1660 1655. Hermitage Museum.

FederFeder. Italiano: Vista Della Torre Del Micalet Dalla Plaza de La Reina, May 18, 2011. Own work. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:El_Micalet.jpg#mediaviewer/File:El_Micalet.jpg.

Greelis, Jim. “Military.” The American Pigeon Museum, n.d. http://www.theamericanpigeonmuseum.org/military-pigeons.html.

Haag-Wackernagel, Daniel. “The Feral Pigeon.” Research Group Integrative Biology, n.d. https://anatomie.unibas.ch/IntegrativeBiology/haag/Culture-History-Pigeon/feral-pigeon-haag.html.

Haupt, Lyanda Lynn. The Urban Bestiary. 1st ed. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company, 2013.

Hawthorne Deming, Alison. Zoologies. 1st ed. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2014.

“History of Valencia.” Spanish Town Guides: Your Complete Guide to Spain, 2011 2002. http://www.spanish-town-guides.com/Valencia_History.htm.

“‘Hope’ Is the Thing with Feathers – (314) by Emily Dickinson : The Poetry Foundation.” Accessed November 12, 2014. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/171619.

Kravtchenko, Viktor. “Rock Pigeon (Columba Livia) Distribution Map.” Wikimedia Commons, July 13, 2008. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Columba_livia_distribution_map.png.

“Letters of Note: FOR HEAVENS SAKE STOP IT.” Accessed October 21, 2014. http://www.lettersofnote.com/2010/05/for-heavens-sake-stop-it.html.

MacKenzie, Donald A. “Chapter XVIII-The Age of Semiramis.” Sacred-Texts.com, 1915. http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/mba/mba24.htm.

Matthews, Caitlín, and John Matthews. “Dove.” The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc., 2005.

Miller, Everett B. “Chapter XVIII.” U.S. Army Medical Department: Officec of Medical History, n.d. http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/wwii/vetservicewwii/chapter18.htm.

Murillo, Bartolomé Esteban. The Annunciation. Oil on canvas, 1660 1655. Hermitage Museum. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bartolom%C3%A9_Esteban_Perez_Murillo_023.jpg.

“Navigation.” The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds, 2007. http://www.birds.cornell.edu/allaboutbirds/studying/migration/navigation.

“Origin and Evolution.” Natural History Museum, n.d. http://www.nhm.ac.uk/nature-online/species-of-the-day/evolution/columba-livia/origin-evolution/index.html.

Petrak, Chris. “Tails of Birding: Pigeons and Doves – Symbolism.” Tails of Birding, March 12, 2011. http://tailsofbirding.blogspot.com/2011/03/pigeons-and-doves-symbolism.html.

“Pigeon (bird).” The Encyclopedia Britannica Online, April 24, 2014. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/460131/pigeon.

“Plaza de La Virgin.” Valencia City Guide, 2014 2005. http://www.valencia-cityguide.com/tips/things-to-do/plaza-de-la-virgen.html.

Portrait of Chaucer, 16th century. British Library. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Chaucer_-_Portrait_and_Life_of_Chaucer_(16th_C),_f.1_-_BL_Add_MS_5141.jpg.

provided, Unknown or not. Attaching a Message to a Signal Corps Carrier Pigeon, circa 1917-18., 1917 – Ca. 1920, ca. 1920 1917. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Attaching_a_message_to_a_Signal_Corps_carrier_pigeon,_circa_1917-18.,_1917_-_ca._1920_-_NARA_-_512434.tif.

Razes, Joe. “Pigeons of War.” America in WWII, August 2007. http://www.americainwwii.com/articles/pigeons-of-war/.

“Rock Pigeon.” The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds, n.d. http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/rock_pigeon/lifehistory.

Rogers, Shannon L. “Dove.” All Things Chaucer an Encyclopedia of Chaucer’s World. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2007. https://login.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/login?url=http://literati.credoreference.com/content/title/abcchaucer.

“Slum Clearence.” Learning Adventures in Citizenship, n.d. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/newyork//laic/episode7/topic3/e7_t3_s2-sc.html.

The Holy Bible. King James Version., n.d.

Thoreau, Henry David. “Walking,” 1862.

Unknown. 1 Middle-Billed Tumbler, by 1914. The New Student’s Reference Work, 5 volumes, Chicago, 1914 (edited by Chandler B. Beach (1839-1928), A.M., associate editor Frank Morton McMurry (1862-1936), Ph.D.). http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LA2-NSRW-3-0536.jpg.

Usher, Shaun. “For Heaven’s Sake Stop It.” Letters of Note, May 5, 2010. http://www.lettersofnote.com/2010/05/for-heavens-sake-stop-it.html.

“Valencia Cathedral: History.” Valencia Cathedral, 2014. http://www.catedraldevalencia.es/en/historia-de-la-catedral.php.

“Valencia (Spain).” Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed November 28, 2014. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/621977/Valencia.