Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar)

Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) is a member of the Salmonidae family that commonly “spends one or more years in river [systems] before migrating” to the North Atlantic Ocean “to grow to adulthood.” (O.F.A.H., 2007: 2) There are other salmon populations, however, that pass their entire lives in freshwater, where they inhabit lakes throughout their adulthood and return to the lake’s tributaries to spawn. Atlantic salmon have a silver colouring with small black dots that are speckled throughout most of their bodies. They turn a deep bronze tone during their spawning season in the fall when they travel upstream (O.F.A.H., 2007).

Carried On Salmon’s Back

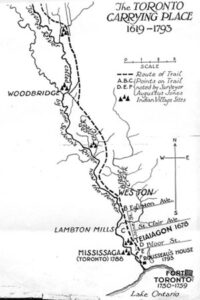

Carried on Salmon’s Back is a pen and ink illustration that represents the historical agency of Atlantic salmon and their impact on the emergence and expansion of First Nations communities, and the establishment of York, on the northern shores of Lake Ontario. The work depicts an original ink map of the Toronto Carrying Place, from 1619-1793. (Figure 1) This site was once a portage route that stretched from the Humber River to the Holland River, and was a vital trade network for First Nations communities for several thousand years. To this day, the significance of Atlantic salmon to the development and expansion of human communities in the Lake Ontario region remains greatly overlooked by many Torontonians and is a history largely unknown except to those who search for it.

The History of Atlantic Salmon in Lake Ontario

(Figure 1) Carrying Place Trail Map. Photo from Historica Canada, courtesy of Taiaiakon Historical Preservation Society.

The origin of Atlantic salmon in Lake Ontario and its tributary rivers and streams can be traced back several thousand years. According to the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters, (O.F.A.H.) Atlantic salmon entered “Lake Ontario from the sea during the post [pleistocene] glacial period” and soon “adapted to life in freshwater conditions” (O.F.A.H., 2007: 3). Following their freshwater adaptation to Lake Ontario and its adjoining waterways, salmon populations increased rapidly and they became the Lake’s top predators. According to the O.F.A.H., these salmon populations were likely to have fed upon lake herring and sculpin (O.F.A.H., 2007: 2). They soon became an important staple for many species that inhabited the region likely due to their abundance and given the fact that they possess “the highest caloric count of any North American fish species” (Dunfield, 1985: 13). In particular, salmon, in addition to eels and catfish, became a vital food source for First Nations communities that resided throughout the Lake Ontario region. For these communities, salmon had vast cultural significance as primary resources for trade and as objects of worship (O.F.A.H., 2007).

The northern shoreline of Lake Ontario was historically inhabited by a number of first nations groups who utilized the region as an important site for trade. Specifically, “the rivers leading out of Lake Ontario (Credit, Rouge, Don Valley, and Humber) attracted people to the shoreline, [primarily] for salmon fishing, and linked inland communities to lakeside ones” (Fiddes, 2014). The Toronto Carrying Place remained the primary route for such trade for several centuries and stretched north from Lake Ontario up the Humber River Valley to the Holland River’s west branch (Fiddes, 2014). According to R. W. Dunfield, “it has been claimed that fishing was the predominant industry” (Dunfield, 1985: 13) of these early communities and that these established fishing communities grew and expanded as a result of their access to salmon. Atlantic salmon later became a vital resource for European settlers who entered the Lake Ontario region in the late 17th century. In addition, it remained an important food source and economic resource during the establishment of the town of York.

Lake Ontario tributaries in which Atlantic salmon were native: circled numbers indicate

where salmon were planted. From Environment Canada (Parsons 1973)

Shortly after the American revolution, a large wave of loyalists migrated to the Lake Ontario region and, in 1792, claimed it as the new colony of Upper Canada. (Dunfield, 1985: 74) It is clear through written records of these early founders of York that they recognized the “potential of the country from a piscatorial point of view” (Dunfield, 1985: 74). According to the work of Isaac Weld, in the early 1790’s Lake Ontario and its adjoining waterways were “abound with excellent salmon and many different kinds of sea fish” (Dunfield, 1985: 74). Another account referencing the abundance of salmon was written on August 4, 1793 by Mrs. John Graves Elizabeth Simcoe, wife of the colony’s first governor:

[quote author=”Dunfield, 1985: 74″]

An Indian named Wable Casigo supplies us with salmon, which the rivers and creeks along this shore abound with. It is supposed they go to sea; the velocity which fish move makes it not impossible, and the very red appearance and the goodness of the salmon confirms the supposition; they are best in the month of June. The species was such a common food source to the early settlers that if one chose not to fish for them oneself, they could be procured as cheaply as the cheapest item. Robert Gourlay reported that “a salmon of ten to twenty pounds brought one shilling, a gill of whiskey, a cake of bread or the like trifle.

[/quote]

Elizabeth Simcoe. From Simcoe Family fonds, Reference Code: F 47-11-1-0-247,

Archives of Ontario, I0007099

These observations were shared by other inhabitants who claimed that the region’s newcomers “made considerable use of [such] resources, and varied their diets by netting large numbers of whitefish, salmon, sturgeon and other species” (Dunfield, 1985: 74). Still, netting as a form of capturing fish was only occasionally practiced, and “salmon were principally taken with the spear in Upper Canada just before the turn of the century” (Dunfield, 1985: 74). According to Dunfield, salmon spearing became a popular sport among boys and men in York, who often engaged in the activity in Toronto Bay (Dunfield, 1985: 74). There are several written records from this time that describe locals observing “many canoes on the Bay in the evening, its occupants fishing by jacklight” (Dunfield, 1985: 74). These hunting practices are further explored in Elizabeth Simcoe’s account of an incident that took place on November 1, at the mouth of the Don River. According to her written account,

[quote author=”Dunfield, 1985: 75″]

At eight this dark evening we went in a boat to see salmon speared. Large torches of whitebirch bark being carried in the boat, the blaze of light attracts the fish, when the men are dexterious in spearing. The manner of destroying the fish is very disagreeable but seeing them swimming in schools around the board is a very pretty sight.

[/quote]

Within his work, “The Literature of Salmo salar in Lake Ontario and Tributary Streams,” William Sherwood Fox argued that “every village along the rivers tributary to the lake feasted on salmon from May to November” (Dunfield, 1985: 75). In addition to the Don River and Toronto bay, the Credit river proved to be a prime salmon fishing location and was a favoured site among local First Nations groups. There are accounts and stories that describe prominent First Nations inhabitants who accessed these waters for fishing. Historian Donald Smith refers to an event in August, 1797, when “Chief Wabakinine, of the Mississaugas of New Credit First Nation, his wife and his sister traveled from the Credit River to York, where St. Laurence Market now stands, to sell salmon” (Sandy, 2013: Salmon). According to Amber Sandy, accounts from early settlers during this time suggest that “the Credit River was once so full of Atlantic salmon that people were able to cross the river by walking on their backs” (Sandy, 2013: Salmon).

From the 1790’s until 1815, Atlantic salmon were harvested in large quantities and their numbers “did not at first appear to diminish rapidly,” and one could easily acquire a “200-pound barrel for a reasonable 30-35 shillings” (Dunfield, 1985: 107). Salmon at the time were reported to weigh from 20 to 60 pounds each and, according to John McCuaig who later became “superintendent of fisheries for Upper Canada, they “swarm[ed] the rivers so thickly, that they were thrown out with the shovel, and even with the hand” (Dunfield, 1985: 107). According to Dunsfield, “the presence of salmon was an important economic factor within the colony: the locations of homesteads and even towns were frequently considered in respect to their proximity to salmon areas” (Dunfield, 1985: 107). This view is expanded upon by O.F.A.H.’s report that suggests that the abundance of salmon “encouraged settlement of the interior of Canada (meaning, at the time, Ontario)” (O.F.A.H., 2007: 3).

Fish Market, Toronto. Engraving by W.H. Bartlett, 1840, copied about

1910. [Cropped] from McCord Museum.

Cyborg 1

Cyborg 1 represents the current dependence of Lake Ontario Atlantic salmon populations on human technology. The production of the roe, fry and smolt that are released into Ontario’s lakes have been achieved through a process of genetic engineering. Their transportation, rearing and release have been achieved through the joint efforts of various social human bodies and institutions. Their ecosystems have been shaped and are monitored and managed by habitat restoration projects. Given this, the presence of Atlantic salmon can in no way be considered separate from the human technological ingenuity that makes their existence in Lake Ontario possible. They are, as Donna Haraway would term, “Cyborgs: cybernetic organisms, hybrid[s] of machine and organism” (Haraway, 1991: 149) whose “lived social and bodily realities” breakdown crucial boundaries and create the potential to re-imagine humanity’s “joint kinship with animals.” (Haraway, 1991: 154)

The Introduction of Atlantic Salmon into Lake Ontario

In 2006, the Ontario Federation of Angers and Hunters, in partnership with the Ministry of Natural Resources, began the ‘Atlantic Salmon Reintroduction Program for Lake Ontario,’ otherwise known as ‘Bring Back the Salmon.’ According to Carolyn Glass, “over 30 organizations have joined together to implement the project’s goal of establishing a self sustaining Atlantic salmon population in Lake Ontario” (Glass, 2010: iii). The ‘Bring Back the Salmon’ restoration project includes four components: “fish production and stocking, water quality and habitat enhancement, outreach and education, and research and monitoring” (As stated on Bring Back the Salmon’s website). The project “is structured in five-year phases,” the first phase having been completed in 2011 with the introduction of more than 2.5 million salmon into three tributaries: the Credit River; Duffins Creek; and, Cobourg Brook (As stated on Bring Back the Salmon’s website). The salmon breeding stock released in these tributaries were originally from the La Have River, Nova Scotia and, “to maximize genetic diversity” the project is “developing and maintaining two new broodstock populations of contrasting characteristics” (O.F.A.H., 2007: 5).

In 2006, the Ontario Federation of Angers and Hunters, in partnership with the Ministry of Natural Resources, began the ‘Atlantic Salmon Reintroduction Program for Lake Ontario,’ otherwise known as ‘Bring Back the Salmon.’ According to Carolyn Glass, “over 30 organizations have joined together to implement the project’s goal of establishing a self sustaining Atlantic salmon population in Lake Ontario” (Glass, 2010: iii). The ‘Bring Back the Salmon’ restoration project includes four components: “fish production and stocking, water quality and habitat enhancement, outreach and education, and research and monitoring” (As stated on Bring Back the Salmon’s website). The project “is structured in five-year phases,” the first phase having been completed in 2011 with the introduction of more than 2.5 million salmon into three tributaries: the Credit River; Duffins Creek; and, Cobourg Brook (As stated on Bring Back the Salmon’s website). The salmon breeding stock released in these tributaries were originally from the La Have River, Nova Scotia and, “to maximize genetic diversity” the project is “developing and maintaining two new broodstock populations of contrasting characteristics” (O.F.A.H., 2007: 5).

In addition to utilizing genetic breeding techniques for fish production, the project has also been engaged in ensuring habitat protection and restoration by introducing the Community Stream Steward Program (C.S.S.P.), a program that is “designed to engage local landowners and provide them with techniques and support to conduct habitat restoration on their lands” (O.F.A.H., 2007: 6). The C.S.S.P. states that it completed “182 habitat projects in 2006 and enhanced the water quality of 7,055m of streams for improved fishing communities and ecosystem health” (O.F.A.H., 2007: 6). In addition, the project anticipates the completion of the following plans:

Tree planting on stream and river banks to decrease erosion and lower water temperatures; Removal of online ponds to reestablish natural channels; Debris removal to restore natural flows and expose suitable salmon and trout habitat (gravel and rock cobble); Bank stabilization projects to minimize erosion and resulting sedimentation of

spawning and nursery areas; Wetland protection to ensure high quality and quantity of water; and Cattle fencing and alternate watering systems to prevent grazing on stream and river banks and in-stream habitat destruction (O.F.A.H., 2007: 6)

The project’s success is also highly dependent on education and outreach activities that include: “informing the public about the history of Atlantic salmon in Ontario, the significance of their return, the role of Atlantic salmon as indicators of watershed health, and how the actions of all residents of the Lake Ontario basin will determine the future of the collective restoration efforts” (O.F.A.H., 2007: 7). As one of their strategies, the project has constructed a classroom hatchery program that invites schools to participate in raising “approximately 40-100 fish for release” (O.F.A.H., 2007: 7).

By representing the project as a successful return of Atlantic salmon to their traditional ecosystem is to overlook their presence as artificially managed by humans, a topic elaborated on in a dissertation titled An Evaluation of the Reintroduction of Atlantic Salmon to Lake Ontario and its Tributaries. According to Carolyn Glass, the original ecosystems that allowed Atlantic salmon to once flourish have since transformed dramatically and “the inherent complexity and dynamic nature of ecosystems make it impossible to fully recreate a historic system” (Glass, 2010: 5). In addition, she states that many believe that the current salmon stocks of “fry, fingerlings, and yearlings” being introduced “do not adequately represent the challenges that the species will [face] once stocking has ceased and they are left to spawn, hatch and develop on their own” (Glass, 2010: 47). As a result, she regards these stocks as “halfway technology’ [that] cannot be considered a long term solution” (Glass, 2010: 47) to Atlantic salmon decline. Instead, to have a sustainable Atlantic salmon population may require these stocks and their management to remain somewhat artificial (Glass, 2010: 59).

Cyborg 2 (Grey Meat)

Atlantic Salmon is considered by many to be one of the best freshwater fish meats in the world. As a result, salmon fillets, steaks and portions are frequently found on restaurant menus, market shelves and in grocery store isles. The well recognized orange colouring of this valued meat is not produced organically, however, but is the result of chemical dies that are “administered to farmed salmon to colour their flesh which would otherwise be grey” (David Suzuki Foundation: 3). As prepared products for consumption, Atlantic salmon are hardly overlooked, however their lives, and the profit-oriented processes that bring them to Toronto consumers, remain a mystery to many.

According to the ‘Guide to Canadian Farmed Salmon,’ “Atlantic salmon account for over 90% of the farmed salmon produced and over 75% of all salmon consumed” (As stated on the Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance webpage) as a result of farming techniques. In Canada, Atlantic salmon is farmed on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. According to work published by the David Suzuki Foundation, these Atlantic salmon farms are primarily located in New Brunswick and “mostly small operators [are stationed in] coastal areas around Vancouver Island, BC” (David Suzuki Foundation: 2)

Salmon farming practices generally involve to use of open netcages that float in “publicly owned coastal waters” (David Suzuki Foundation: 2) in which salmon are raised in densely packed conditions. As a result, the salmon raised “require the use of antibiotics and other drugs to control disease, and traces of these substances [can be] passed on to consumers.” (David Suzuki Foundation: 3) Among these diseases, “Infectious salmon anaemia (ISA) is the most common, and deadly,” and has led to several outbreaks in New Brunswick fish farms. Furthermore, BC fish farms “import Atlantic salmon eggs from the east coast, increasing the threat of ISA in BC” (David Suzuki Foundation: 3). In addition to these concerns, research conducted on wild BC sockeye salmon by biologist Alexandra Morton has uncovered the presence of other deadly salmon viruses and diseases, including the piscine reovirus that have spread from salmon farms in the region. These findings were presented in the documentary Salmon Confidential. Although it remains difficult to determine the source of the virus, similar strands of the piscine rio-virus were first discovered in Norwegian Atlantic salmon farms, and studies demonstrate that this virus has since been detected in Norway’s wild Atlantic salmon (Garseth et al., 2012)

References:

- Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance

Your Quick Guide to Canadian Farmed Salmon. http://www.aquaculture.ca/files/GuidetoCanadianFarmedSalmon.pd - David Suzuki Foundation

Salmon Aquaculture (Brochure). David Suzuki Foundation: Vancouver. http://www.davidsuzuki.org/publications/downloads/Aquabrochure.pdf. - Dunfield, R.W.

1985. The Atlantic Salmon in the History of North America. Department of Fisheries and Oceans: Halifax. - Fiddes, Jenny.

- 2014. Lake Ontario. First Story Toronto: Exploring the Aboriginal History of Toronto (Blog). https://firststoryblog.wordpress.com/

- Garseth ÅH, Fritsvold C, Opheim M, Skjerve E, Biering E.

2012. Piscine reovirus (PRV) in wild Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., and sea-trout, Salmo trutta L., in Norway. Journal Fish Disease. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23167652 - Glass, Carolyn

2010 “An Evaluation of the Reintroduction of Atlantic Salmon to Lake Ontario and its Tributaries.” Master’s Thesis, Environment and Resource Studies, University of Waterloo. - Haraway, Donna

1991. A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist- Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century In Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. pp.149-181. New York: Routledge, - Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters

2007. Lake Ontario Atlantic Salmon Restoration Program History and Overview. Toronto: O.F.A.H. - Sandy, Amber

2013. St. Laurence Market and the story of Chief Wabakinine. First Story Toronto: Exploring the Aboriginal History of Toronto (Blog). https://firststoryblog.wordpress.com/tag/salmon/